Entertainment

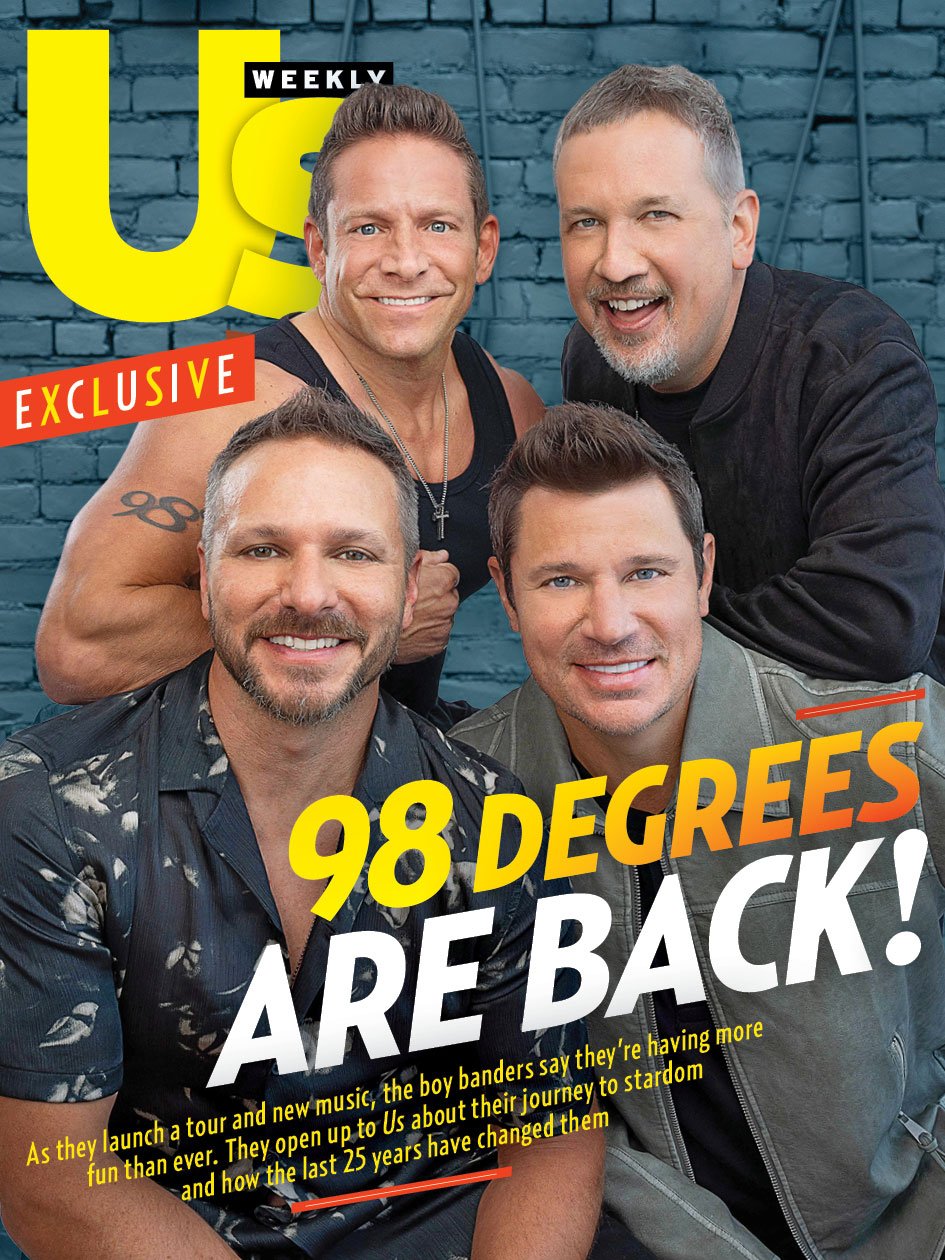

98 Degrees on New Music, ’90s Style and Being a ‘Blue-Collar Boy Band’ on September 13, 2023 at 12:00 pm Us Weekly

In their heyday, 98 Degrees sold nearly 15 million records, had four top 10 singles and regularly graced the covers of teen magazines alongside the likes of ’NSync and the Backstreet Boys. Despite their outsize fame, Ohio natives Drew and Nick Lachey, Jeff Timmons and Justin Jeffre say they never took success for granted — or stopped hustling. “We call ourselves the blue-collar boy band,” shares Drew. Adds Nick, “Our mindset was always, ‘You might out-dance us, you might out-sing us, but you sure as hell won’t out-work us.’ We got discovered the old-school way, singing for money and food. I’m very proud of how we came up.”

More than two decades later, Drew, 47, Nick, 49, Jeff, 50, and Justin, also 50, are still grinding. Now managed by Johnny Wright of Wright Entertainment Group, they’re working on new music, embarking on a 25th Anniversary Tour and, they tell Us exclusively, rerecording their masters. But today, they’re better able to enjoy the fruits of their labor. “We’re more relaxed,” says Jeff, the band’s founding member. “Everything is more fun.” The guys sat down with Us at the Hotel Covington in Covington, Kentucky, to talk about their early days, returning to the studio and their unbreakable bond.

It’s been 25 years since you guys broke out onto the scene. How exciting is that?

DREW It’s one of these moments where you have to look back. It’s like, “Has it really been that long?” In some ways, it seems like just yesterday that we got together.

How did you initially form the band?

JEFF We started it ourselves. You didn’t have YouTube or American Idol back then. I went to L.A. with some other guys, and they dropped out. Then I was introduced to Nick. When I heard his voice, I was like, “I’ve got to get this guy out here.” I didn’t even know what he looked like…

DREW Otherwise he never would’ve called him!

JEFF I tricked him into coming out to L.A. I lied and said I had a lot of stuff going on even though I had nothing. He brought Justin and Drew with him, and that’s how we got started.

“We never really thought of ourselves as a boy band,” says Nick. “We just got swept up in the current.” John Chapple/MEGA

Did you instantly know that you had something special?

DREW We had something different. We pride ourselves on our vocals, and we’d rehearse nonstop, just a capella and harmony. It didn’t come without a lot of effort and hard work.

NICK There are a lot of great singers out there, but it doesn’t automatically lend itself to harmonizing. So I think when people heard our harmonies, it was like, “Wow, OK.” It set us apart from other bands that were out trying to do the same thing.

How did you decide on the name 98 Degrees?

DREW We voted on it. We wanted something that represented the mood and tone.

Can you share some band names that didn’t make the cut?

JUSTIN There’s a long list. Spontaneous Combustion was a personal favorite.

NICK I still stand by Inertia. What did we start out as?

JEFF It was Just Us. First Four was another one.

DREW Which was terrible. [There was also] Next Issue.

You had your first hit with “Invisible Man” in 1997. Did it feel like success came quickly?

JEFF It felt like it took forever. We got signed in ‘95 and recorded all of ’95 and ’96. We came out in ’97, but we weren’t really marketed. We weren’t on MTV. Our label was Motown, and they didn’t want to put our pictures on anything — they wanted to keep this mystique that we were an R&B group. It took another album and TRL to come out, and then that exposure happened in ’98 and ’99.

JUSTIN Once you’re signed, you realize, “Oh, that doesn’t mean you made it.” It’s still a lot of work ahead.

What was the moment when you felt like you’d finally made it?

NICK We were in Asia touring, and I vividly remember I was in the hallway of our hotel, and Jeff came out and said, “‘Because of You’ just went Top 10.”

DREW Then you’re like, “Alright, are we going to be a one-hit wonder?” So you have to continue grinding and promoting.

NICK We didn’t have the easiest road. We weren’t put together by some magical guy putting pieces in.

“We felt pressure amongst each other just to make it,” says Jeff. “We were pretty hard on each other.” John Chapple/MEGA

There were a lot of boy bands vying to be No. 1. Did you feel any rivalry with them?

JEFF We thought we were more of an R&B vocal group. Not to disparage those bands — we love them, we were friends with all of them — but we thought we were different. Once the media started saying, “Well, you’re like Backstreet Boys and ’N Sync,” then we were like, “Oh, do we need to start dancing more?”

NICK It was a blessing and a curse. There was so much momentum behind the boy band craze, and it was nice to get caught up in that, but it also caused pressure.

To achieve a certain level of success?

DREW There was this completely unattainable bar that was set. People don’t come out and sell 2 million records in the first week — that’s an anomaly.

JEFF There was an article about how our next record was about to come out after Britney [Spears] and Backstreet Boys and ’N Sync consecutively broke records, and it said 98 Degrees is set to do it next. Sadly, we only sold 536,000 records in the first week, and it was a big disappointment.

DREW At this point, we have a better perspective on it all. We enjoy the moment more. We put out projects we’re happy with, and whatever happens with them, happens.

Which song are you most proud of?

NICK “Invisible Man” will always have a special place in my heart. It brings back memories of calling the radio station as you’re driving your motorhome down the highway, requesting your own song.

JEFF They’d call you out. “Is this 98 Degrees?” I hung up the phone immediately. “Because of You” is also a good one. Once that took off, we were everywhere.

What was that like — being thrust into the spotlight?

DREW It was awesome but also overwhelming. I kicked a hole in a wall at one venue because I was so frustrated. I had to pay for the repairs!

Did you all keep each other in check?

NICK You become a brotherhood in all the best ways — and sometimes not the best ways. You lean on each other. To have my own brother in the band was very cool for me — he might say it wasn’t for him [laughs] — but it’s fun to go through it together. Getting chased out of a mall in the Philippines — if you were by yourself, it wouldn’t be nearly as much fun.

Clockwise: Nick Lachey, Drew Lachey, Justin Jeffre, Jeff Timmons John Chapple/MEGA (4)

Any major fights through the years?

DREW [Most] of our disagreements were about which song should be a single or which deal to sign. It wasn’t like, “Oh, you stole money from me.”

NICK There was the Kinder egg incident.

JEFF We were in Germany. I was bored. At every stop, I’d get Kinder eggs — these chocolate eggs with a prize in them. I was opening them and playing with the prizes, but not eating the chocolate. It was super-annoying to the guys — chocolate and wrappers everywhere. They kept stepping on them. They wanted to kill me.

NICK If anything, we’re guilty of being too nice to each other. We probably could’ve used a few more air-the-dirty-laundry fights.

What led to your 2002 hiatus?

JUSTIN We’d just been on the road for so long. We were ready to have more of our own lives outside of the group.

What brought you back together?

DREW We had an opportunity to go back out on the road with New Kids on the Block and Boyz II Men. That was the nudge we needed.

Do you guys ever watch your old music videos?

DREW I went back before this new run of shows. There were moments when I was like, “Oh, my God, I forgot that happened!” We have kids who are old enough to understand it. They’re like, “What was that?” Well, kids, this is a VCR with a VHS tape. [Laughs.] It’s fun to walk down memory lane.

Any regrettable fashion moments?

NICK So many to choose from. It was bad skin, bad outfits, a lot of bad hair. It was just a lot of bad choices.

Do your kids listen to your music?

DREW They don’t listen to it at all. For the most part, It’s other people that I work with who are of that age that look up the videos on YouTube and think it’s fun. My kids are just like, “Oh my God, how many concerts do we have to sit through?”

NICK My kids hate when I sing.

JEFF My kids like it a bit, but they’re over it — they’ve been to too many concerts. They like Little Uzi Vert or whatever.

“It ranks up there as one of our worst fashion moments,” Drew says about their looks at the 1998 Mulan premiere. Frank Trapper/Corbis via Getty Images

Justin, are you still living the bachelor life?

JUSTIN My girlfriend has a son, so it feels a bit like there’s a fatherly role — but fortunately, it’s more like I get to be the cool dad.

How’s it being back on the road?

DREW We have a different take on touring now. It’s about [figuring out] what amount of time we feel comfortable being away and how we can route the tour so we can bring our families.

Who forgets the lyrics most when you’re performing?

DREW Nick. In his defense, he has the most lyrics to sing!

NICK But I’ll always sing something! I’ll improvise. It may not be the actual lyric, and our fans will call me out, but it’s proof we’re singing live.

How do your wives feel about you being on tour?

DREW They’re like, “Go, bye!” [Laughs.] They’re supportive. There are moments our families like to be a part of, and those are the moments you really hold on to.

We’ve all grown and evolved and changed and challenged ourselves,” says Drew. “So we’re bringing new skill sets into the group now.” John Chapple/MEGA

Tell Us about your new music.

JEFF We’ve tried a few things that might not have been our lane. And you see these different things, and the evolution of music. The new music has new sounds in it, but I think the inspiration is our old stuff.

DREW Yeah, we sing love songs. Ultimately, that’s what we do. That’s what we’re most comfortable with, and that’s what we’re best doing.

JEFF My wife is a boy band fan now. Sadly she’s more of a New Kids On The Block fan, but that’s a good test market. So I will run songs by her and she’ll say yay or nay.

You’re rerecording songs as well.

JEFF Record companies traditionally do deals where they take percentages of everything. Ours, EX1, is partnering with us and allowing us to own parts of our masters, and we’re re-recording some of our old hits. It’s exciting.

All of you are working on solo projects as well across entertainment and business.

DREW We’re all exploring other opportunities. In the past [being in the band] was all-consuming. We learned that you have to have other things that inspire you and move you outside of just this group. So yeah, we’re all hustling on our own too.

What do you like to do when you’re not working?

DREW I have a side business with my wife. And my son and daughter are a part of that as well.

JEFF Just normal dad stuff. When you do this for so long, that’s kind of our vacation — getting to be with your family and experiencing sports and choir and cheerleading.

NICK My favorite thing to do with my kids is taking them to school. It’s just the things you talk about, the conversations that come up, the laughing, the music.

“So many parents tell us they were happy to have music that they didn’t feel awkward hearing in the car,” shares Justin. John Chapple/MEGA

There’s a rumor that the Super Bowl halftime show will feature a bunch of boy bands — 98 Degrees, Backstreet Boys, Boyz II Men. Would you be up for that?

NICK We’d love for that to happen.

Boy bands are having a resurgence. Why do you think fans keep coming back for more?

DREW I think it’s just going back to a simpler time. The music was fun. The world seemed a bit safer and less divided, and the shows are upbeat and energetic and bring joy to people.

What do you hope your legacy will be?

JEFF Our reputation and our work ethic — as well as the music — those are the key things.

DREW We’ve always tried to treat people well. We went through this industry, and we took our lumps, but we did it with dignity and respect.

JUSTIN Many parents talk about how they were just happy to have music that they didn’t feel awkward hearing in the house and in the car, so I think that we’re proud of that.

You’ve got the new tour, a new label and new music. What else do you hope to accomplish together?

DREW We want to do music and a show we’re proud of and just appreciate the ride.

NICK If we start sucking, we’ll be like, “OK, guys. it’s time to hang it up.” But as long as we still feel like we can have fun with it and be good at it, why stop?

In their heyday, 98 Degrees sold nearly 15 million records, had four top 10 singles and regularly graced the covers of teen magazines alongside the likes of ’NSync and the Backstreet Boys. Despite their outsize fame, Ohio natives Drew and Nick Lachey, Jeff Timmons and Justin Jeffre say they never took success for granted —

Us Weekly Read More

Entertainment

When “Professional” Means Silent

Michael B. Jordan and Delroy Lindo did not walk onto the BAFTA stage expecting to become a case study in how the industry mishandles racism in real time. They were there to present, hit their marks, and do what award shows have always asked of Black talent: bring charisma, sell the moment, keep the night moving.

Instead, while they stood under the lights, a man in the audience shouted the N‑word. The word carried across the theater and through the broadcast. The cameras kept rolling. The teleprompter kept scrolling. And the two men at the center of it did what they’ve been trained their entire careers to do: they kept going.

The incident was shocking, but the pattern around it was familiar.

The Apologies That Came After the Credits

In the days that followed, BAFTA released a public apology. The organization said it took responsibility for putting its guests “in a very difficult situation,” acknowledged that the word used carries deep trauma, and apologized to Michael B. Jordan and Delroy Lindo. It also praised them for their “dignity and professionalism” in continuing to present.

The man who shouted the slur, a Tourette syndrome campaigner, explained that his outbursts are involuntary and expressed remorse for the pain his tic caused. That context about disability matters. Any honest conversation has to hold space for the reality that not every harmful word is spoken with intent.

But context doesn’t erase impact. For people watching at home—and especially for the men on that stage—the sequence was still the same: a slur detonated in the room, the show continued as if nothing happened, and the institutional response arrived later, in carefully crafted language.

Delroy Lindo summed up the experience by saying he and Jordan “did what we had to do,” and added that he wished someone from the organization had spoken with them directly afterward. That gap between polished statements and real‑time care is exactly where trust breaks down.

Who Is “Professionalism” Really Protecting?

Strip away the PR and a hard truth emerges: almost all of the pressure fell on the people who were harmed, not the people in charge.

On stage, “professionalism” meant Jordan and Lindo were expected to stay composed so the room wouldn’t be uncomfortable. Off stage, “professionalism” meant the institution focused on managing optics after the fact instead of disrupting the show in the moment.

That raises a question the industry rarely wants to confront:

When we call for professionalism, whose comfort are we protecting?

For Black artists, professionalism has too often meant:

- Take the hit and keep your face neutral.

- Don’t make it awkward for the audience or the brand.

- Don’t risk being labeled “difficult,” no matter how blatant the disrespect.

It’s easy to admire that composure. It’s harder to admit that the system routinely demands it from the very people absorbing the harm.

If It Can Happen There, It Can Happen Anywhere

This didn’t happen in a chaotic open mic or an unsupervised live stream. It happened at one of the most carefully produced film ceremonies in the world—an event with run‑of‑show documents, stage managers, and communication channels in everyone’s ears.

If an incident like this can unfold there without a pause, it can unfold anywhere:

- At a regional festival Q&A when an audience member crosses a line.

- At a comedy show when someone heckles with a “joke” that’s really just a slur.

- At a film panel where the only Black creator on stage gets a loaded question and is expected to smile through it.

The honest question for anyone who runs events isn’t “How could BAFTA let this happen?” It’s “What would we actually do if it happened in our room?”

Would your moderator know they have explicit permission to stop everything?

Would your team know who goes to the stage, who speaks to the audience, and who stays with the person targeted?

Or would you also be scrambling to get the language right in a statement tomorrow?

Redefining Professionalism in 2026

If this moment is going to mean anything, the definition of professionalism has to change.

Professionalism cannot just be “don’t lose your cool on stage.” It has to include the courage and structure to protect the people on that stage when something goes wrong.

A better standard looks like this:

- Pause the show when serious harm happens. A clean program is not more important than a person’s dignity.

- Acknowledge it in the room. Name what happened in clear terms instead of pretending it didn’t occur and quietly editing it later.

- Center the person targeted. Check on them, give them options, and let their comfort—not the schedule—drive the next move.

- Plan the response before you need it. Build safety and harassment protocols into your festival, awards show, or live event so no one is improvising under pressure.

Sometimes the most professional thing you can do is allow a little discomfort in the room. It signals that human beings matter more than the illusion of seamlessness.

The Standard Going Forward

Michael B. Jordan and Delroy Lindo did what they have always been rewarded for doing: they protected the show. They shouldn’t have had to.

True respect for their craft and humanity would have looked like a room that moved to protect them instead—stopping the script, resetting the energy, and making it clear that the problem wasn’t their reaction, but the harm they’d just absorbed.

No performer should be asked to choose between their dignity and their career. So if you work anywhere in this industry—onstage or behind the scenes—this incident quietly handed you a new baseline:

Call it out.

Pause the show.

Back the person who was harmed.

That’s what professionalism should mean in 2026.

Entertainment

These Movies Aren’t “True Crime for Fun”

When scandals and cover‑ups dominate the timeline, it’s tempting to process them the same way we process everything else online: as content.

A headline becomes a meme, a victim becomes a character, and a years‑long story of abuse or corruption gets flattened into a 30‑second clip. In that kind of environment, it matters what we choose to watch—and how we watch it.

Some films lean into shock and spectacle. Others slow us down, asking us to sit with the systems that make these stories possible in the first place.

This article is about that second group.

Below are three films that are difficult, necessary, and deeply relevant when we’re surrounded by conversations about power, silence, and who actually gets held accountable. They’re not “true crime for fun.” They are stories about people who push back: journalists digging through archives, lawyers refusing to look away, and insiders who decide that telling the truth matters more than staying comfortable.

Why movies about accountability matter right now

There’s a difference between consuming tragedy and engaging with it.

Scroll culture trains us to treat everything as a quick hit: outrage, reaction, move on. But systemic abuse and corruption don’t work on a 24‑hour cycle. They live in sealed files, non‑disclosure agreements, money, and relationships that make it easier to protect those in power than the people they harm. Films that focus on accountability rather than spectacle can do three important things:

- Slow our attention down long enough to see how cover‑ups are built—through policies, reputations, and quiet decisions, not just villains and heroes.

- Give us a closer look at the people trying to break those systems open: reporters, lawyers, whistleblowers, survivors, and community members.

- Help us recognize the patterns so that when a new scandal breaks, we have more than vibes and rumors to work with—we see mechanisms, not just headlines.

With that frame in mind, here are three films that are worth revisiting or discovering for the first time.

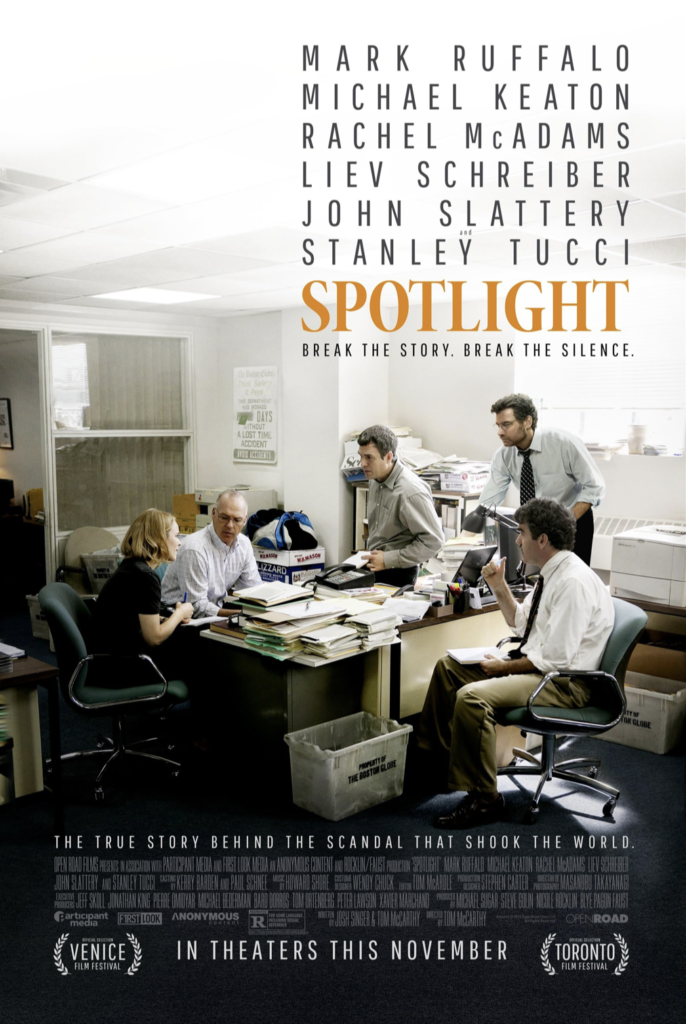

Spotlight: following the paper trail

Spotlight follows a small investigative team at a Boston newspaper as they uncover decades of child abuse inside the Catholic Church and the institutional effort to conceal it. It’s not flashy. There are no chase scenes, no “big twist.” The tension comes from phone calls that aren’t returned, doors that stay closed, and documents that may or may not exist. That’s the point.

The power of Spotlight is in its realism. The journalists don’t “win” through a single heroic act; they win through months of stubborn, often boring work—checking names, cross‑referencing records, going back to survivors who have every reason not to trust them. The film shows how systems protect themselves: not only through powerful leaders, but through a culture of looking away, minimizing harm, or deciding that “now isn’t the right time” to publish the truth.

Watching it in the context of any modern scandal is a reminder that revelations don’t come out of nowhere. Someone has to decide that the story is worth their career, their sleep, their peace. Someone has to keep calling.

Dark Waters: the cost of not looking away

In Dark Waters, a corporate defense lawyer discovers that a chemical company has been poisoning a community for years. The more he learns, the less plausible it becomes to stay on the side he’s paid to protect. What starts as a single client and a stack of records becomes a decades‑long fight against a corporation with far more money, influence, and time than he has.

The film is heavy—not because of graphic imagery, but because of the slow realization that this could happen anywhere. It shows how corporate harm doesn’t usually look like one dramatic event; it looks like small decisions, tolerated over time, because changing course would be expensive or embarrassing. Internal memos, risk calculations, and legal strategies become characters in their own right.

What makes Dark Waters important in this moment is the way it illustrates complicity. Very few people in the film set out to be “villains.” Many are simply doing their jobs, protecting their company, or choosing the convenient version of the truth. The story forces us to ask uncomfortable questions about where we draw our own lines—and what it costs to cross them.

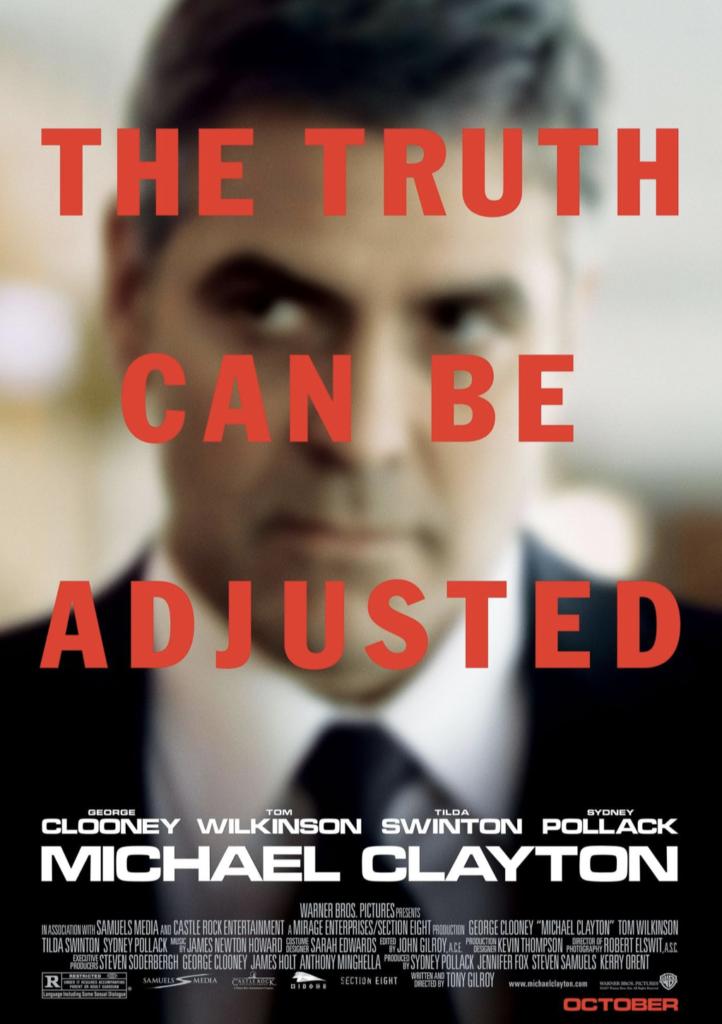

Michael Clayton: inside the clean‑up machine

If Spotlight looks at journalism and Dark Waters at corporate litigation, Michael Clayton focuses on the people whose job is to make problems disappear. The title character is a “fixer” at a prestigious law firm: he isn’t in court, and his name isn’t on the building, but he is the person they call when a client’s mess threatens to become public.

The film peels back the layers of how reputations are maintained. We see how language is used to soften reality—harm becomes “exposure,” victims become “plaintiffs,” and the goal is not necessarily to find the truth but to manage it. When Clayton begins to understand the scale of what his client has done, he faces a question at the core of a lot of modern scandals: what happens when someone inside the machine decides not to play their part anymore?

Michael Clayton is especially resonant when conversations online focus on “who knew” and “who helped.” It reminds us that entire careers and infrastructures exist to protect power and to make sure certain stories never catch fire in the first place.

How to watch these films with care

Because these movies deal with abuse, corruption, and betrayal, they can be emotionally heavy—especially for people who have personal experience with similar harms. A few ways to approach them thoughtfully:

- Check in with yourself before you press play. It’s okay to wait until you’re in a better headspace.

- Watch with someone you trust, or plan a debrief after. These aren’t background‑noise films; they merit conversation.

- Remember that survivors’ experiences are not plot devices. If a conversation about the movie starts turning into speculation or jokes about real people, you have permission to pull it back or step away.

The goal isn’t to turn real‑world pain into “content you can feel good about watching.” It’s to understand the systems around that pain more clearly and to keep our empathy intact.

Why sharing this kind of list matters

Sharing watchlists online can feel trivial, but small choices add up. When we recommend movies that take harm seriously, we’re nudging the culture in a different direction than the endless churn of sensational docuseries and clips built around shock value.

A thoughtful share says:

- I’m paying attention to the structures behind the headlines, not just the gossip.

- I’m interested in stories that center accountability, not just spectacle.

- I want our conversations to honor victims and the people fighting for the truth.

If you decide to post about these films, you don’t have to mention any specific scandal or case at all. You can simply say: “If you’re thinking a lot about power, silence, and cover‑ups right now, these are worth your time.” That alone can open up more grounded, respectful conversations than another round of speculation and rumor.

In a feed full of noise, choosing to highlight stories of persistence, investigation, and courage is its own quiet statement.

Business

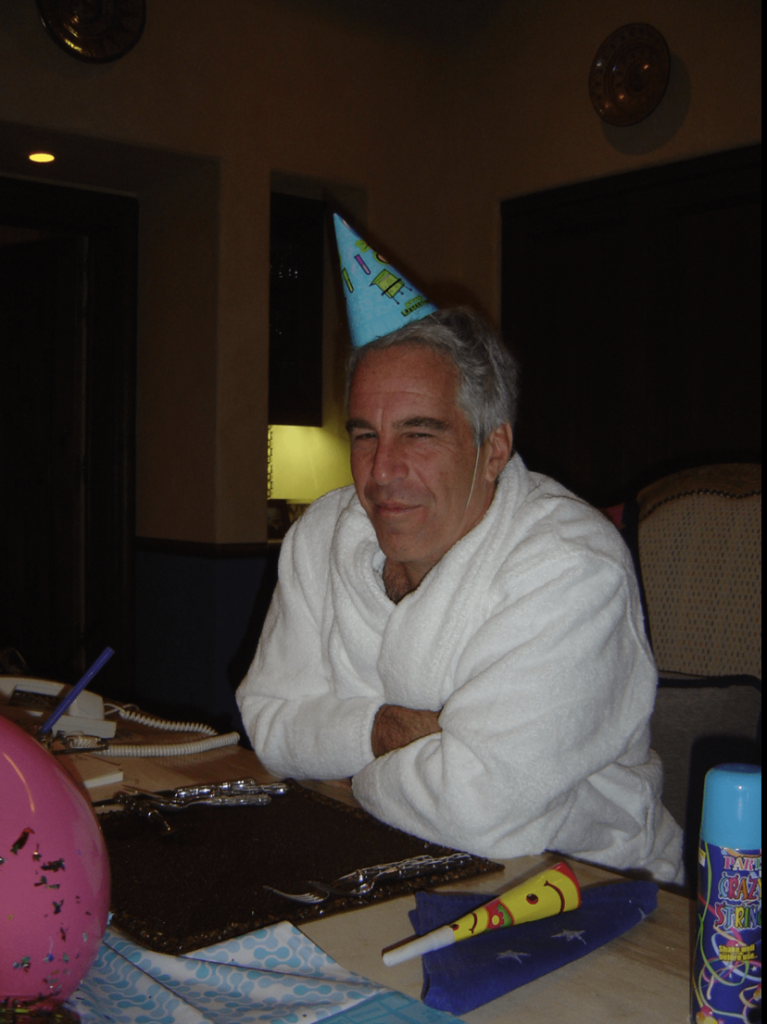

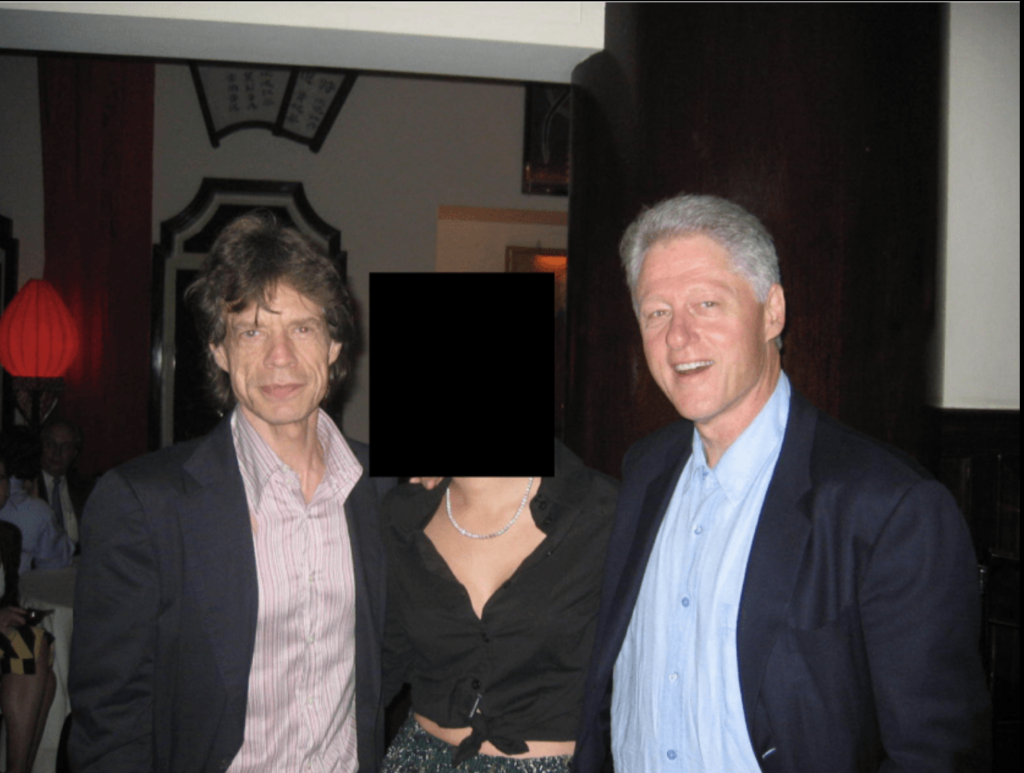

How Epstein’s Cash Shaped Artists, Agencies, and Algorithms

Jeffrey Epstein’s money did more than buy private jets and legal leverage. It flowed into the same ecosystem that decides which artists get pushed to the front, which research gets labeled “cutting edge,” and which stories about race and power are treated as respectable debate instead of hate speech. That doesn’t mean he sat in a control room programming playlists. It means his worldview seeped into institutions that already shape what we hear, see, and believe.

The Gatekeepers and Their Stains

The fallout around Casey Wasserman is a vivid example of how this works. Wasserman built a powerhouse talent and marketing agency that controls a major slice of sports, entertainment, and the global touring business. When the Epstein files revealed friendly, flirtatious exchanges between Wasserman and Ghislaine Maxwell, and documented his ties to Epstein’s circle, artists and staff began to question whose money and relationships were quietly underwriting their careers.

That doesn’t prove Epstein “created” any particular star. But it shows that a man deeply entangled with Epstein was sitting at a choke point: deciding which artists get representation, which tours get resources, which festivals and campaigns happen. In an industry built on access and favor, proximity to someone like Epstein is not just gossip; it signals which values are tolerated at the top.

When a gatekeeper with that history sits between artists and the public, “the industry” stops being an abstract machine and starts looking like a web of human choices — choices that, for years, were made in rooms where Epstein’s name wasn’t considered a disqualifier.

Funding Brains, Not Just Brands

Epstein’s interest in culture didn’t end with celebrity selfies. He was obsessed with the science of brains, intelligence, and behavior — and that’s where his money begins to overlap with how audiences are modeled and, eventually, how algorithms are trained.

He cultivated relationships with scientists at elite universities and funded research into genomics, cognition, and brain development. In one high‑profile case, a UCLA professor specializing in music and the brain corresponded with Epstein for years and accepted funding for an institute focused on how music affects neural circuits. On its face, that looks like straightforward philanthropy. Put it next to his email trail and a different pattern appears.

Epstein’s correspondence shows him pushing eugenics and “race science” again and again — arguing that genetic differences explain test score gaps between Black and white people, promoting the idea of editing human beings under the euphemism of “genetic altruism,” and surrounding himself with thinkers who entertained those frames. One researcher in his orbit described Black children as biologically better suited to running and hunting than to abstract thinking.

So you have a financier who is:

- Funding brain and behavior research.

- Deeply invested in ranking human groups by intelligence.

- Embedded in networks that shape both scientific agendas and cultural production.

None of that proves a specific piece of music research turned into a specific Spotify recommendation. But it does show how his ideology was given time, money, and legitimacy in the very spaces that define what counts as serious knowledge about human minds.

How Ideas Leak Into Algorithms

There is another layer that is easier to see: what enters the knowledge base that machines learn from.

Fringe researchers recently misused a large U.S. study of children’s genetics and brain development to publish papers claiming racial hierarchies in IQ and tying Black people’s economic outcomes to supposed genetic deficits. Those papers then showed up as sources in answers from large AI systems when users asked about race and intelligence. Even after mainstream scientists criticized the work, it had already entered both the academic record and the training data of systems that help generate and rank content.

Epstein did not write those specific papers, but he funded the kind of people and projects that keep race‑IQ discourse alive inside elite spaces. Once that thinking is in the mix, recommendation engines and search systems don’t have to be explicitly racist to reproduce it. They simply mirror what’s in their training data and what has been treated as “serious” research.

Zoomed out, the pipeline looks less like a neat conspiracy and more like an ecosystem:

- Wealthy men fund “edgy” work on genes, brains, and behavior.

- Some of that work revives old racist ideas with new data and jargon.

- Those studies get scraped, indexed, and sometimes amplified by AI systems.

- The same platforms host and boost music, video, and news — making decisions shaped by engagement patterns built on biased narratives.

The algorithm deciding what you see next is standing downstream from all of this.

The Celebrity as Smoke Screen

Epstein’s contact lists are full of directors, actors, musicians, authors, and public intellectuals. Many now insist they had no idea what he was doing. Some probably didn’t; others clearly chose not to ask. From Epstein’s perspective, the value of those relationships is obvious.

Being seen in orbit around beloved artists and cultural figures created a reputational firewall. If the public repeatedly saw him photographed with geniuses, Oscar winners, and hit‑makers, their brains filed him under “eccentric patron” rather than “dangerous predator.”

That softens the landing for his ideas, too. Race science sounds less toxic when it’s discussed over dinner at a university‑backed salon or exchanged in emails with a famous thinker.

The more oxygen is spent on the celebrity angle — who flew on which plane, who sat at which dinner — the less attention is left for what may matter more in the long run: the way his money and ideology were welcomed by institutions that shape culture and knowledge.

What to Love, Who to Fear

The point is not to claim that Jeffrey Epstein was secretly programming your TikTok feed or hand‑picking your favorite rapper. The deeper question is what happens when a man with his worldview is allowed to invest in the people and institutions that decide:

- Which artists are “marketable.”

- Which scientific questions are “important.”

- Which studies are “serious” enough to train our machines on.

- Which faces and stories are framed as aspirational — and which as dangerous.

If your media diet feels saturated with certain kinds of Black representation — hyper‑visible in music and sports, under‑represented in positions of uncontested authority — while “objective” science quietly debates Black intelligence, that’s not random drift. It’s the outcome of centuries of narrative work that men like Epstein bought into and helped sustain.

No one can draw a straight, provable line from his bank account to a specific song or recommendation. But the lines he did draw — to elite agencies, to brain and music research, to race‑obsessed science networks — are enough to show this: his money was not only paying for crimes in private. It was also buying him a seat at the tables where culture and knowledge are made, where the stories about who to love and who to fear get quietly agreed upon.

A Challenge to Filmmakers and Creatives

For anyone making culture inside this system, that’s the uncomfortable part: this isn’t just a story about “them.” It’s also a story about you.

Filmmakers, showrunners, musicians, actors, and writers all sit at points where money, narrative, and visibility intersect. You rarely control where the capital ultimately comes from, but you do control what you validate, what you reproduce, and what you challenge.

Questions worth carrying into every room:

- Whose gaze are you serving when you pitch, cast, and cut?

- Which Black characters are being centered — and are they full humans or familiar stereotypes made safe for gatekeepers?

- When someone says a project is “too political,” “too niche,” or “bad for the algorithm,” whose comfort is really being protected?

- Are you treating “the industry” as a neutral force, or as a set of human choices you can push against?

If wealth like Epstein’s can quietly seep into agencies, labs, and institutions that decide what gets made and amplified, then the stories you choose to tell — and refuse to tell — become one of the few levers of resistance inside that machine. You may not control every funding source, but you can decide whether your work reinforces a world where Black people are data points and aesthetics, or one where they are subjects, authors, and owners.

The industry will always have its “gatekeepers.” The open question is whether creatives accept that role as fixed, or start behaving like counter‑programmers: naming the patterns, refusing easy archetypes, and building alternative pathways, platforms, and partnerships wherever possible. In a landscape where money has long been used to decide what to love and who to fear, your choices about whose stories get light are not just artistic decisions. They are acts of power.

Advice2 weeks ago

Advice2 weeks agoHow to Make Your Indie Film Pay Off Without Losing Half to Distributors

Business3 weeks ago

Business3 weeks agoHow Epstein’s Cash Shaped Artists, Agencies, and Algorithms

Entertainment4 weeks ago

Entertainment4 weeks agoWhat Epstein’s Guest Lists Mean for Working Filmmakers: Who Do You Stand Next To?

Film Industry2 weeks ago

Film Industry2 weeks agoWhy Burnt-Out Filmmakers Need to Unplug Right Now

Business3 weeks ago

Business3 weeks agoNew DOJ Files Reveal Naomi Campbell’s Deep Ties to Jeffrey Epstein

Entertainment3 weeks ago

Entertainment3 weeks agoYou wanted to make movies, not decode Epstein. Too late.

Business & Money4 weeks ago

Business & Money4 weeks agoGhislaine Maxwell Just Told Congress She’ll Talk — If Trump Frees Her

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoHarlem’s Hottest Ticket: Ladawn Mechelle Taylor Live