Business

New York Times-ChatGPT lawsuit poses new legal threats to artificial intelligence on January 9, 2024 at 11:00 am Business News | The Hill

After a year of explosive growth, generative artificial intelligence (AI) may be facing its most significant legal threat yet from The New York Times.

The Times sued Microsoft and OpenAI, the company behind the popular ChatGPT tool, for copyright infringement shortly before the new year, alleging the companies impermissibly used millions of its articles to train their AI models.

The newspaper joins scores of writers and artists who have sued major technology companies in recent months for training AI on their copyrighted work without permission. Many of these lawsuits have hit road bumps in court.

However, experts believe The Times’s complaint is sharper than earlier AI-related copyright suits.

“I think they have learned from some of the previous losses,” Robert Brauneis, a professor of intellectual property law at the George Washington University Law School, told The Hill.

The Times lawsuit is “a little bit less scattershot in their causes of action,” Brauneis said.

“The attorneys here for the New York Times are careful to avoid just kind of throwing up everything against the wall and seeing what sticks there,” he added. “They’re really concentrated on what they think will stick.”

Transformation vs. Reproduction

Generative AI models require mass amounts of material for training. Large language models, like OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Microsoft’s Copilot, use the material they are trained on to predict what words are likely to follow a string of text to produce human-like responses.

Typically, these AI models are transformative in nature, said Shabbi Khan, co-chair for the Artificial Intelligence, Automation, and Robotics group at law firm Foley & Lardner.

“If you asked it a general query …. it doesn’t do a search and find the right passage and just reproduce the passage,” Kahn explained. “It will try to probabilistically create its own version of what needs to be said based on a pattern that it sort of picks up through parsing billions of words of content.”

However, in its suit against OpenAI and Microsoft, the Times alleges the AI models developed by the companies have “memorized” and can sometimes reproduce chunks of the newspaper’s articles.

“If individuals can access The Times’s highly valuable content through Defendants’ own products without having to pay for it and without having to navigate through The Times’s paywall, many will likely do so,” the lawsuit reads.

“Defendants’ unlawful conduct threatens to divert readers, including current and potential subscribers, away from The Times, thereby reducing the subscription, advertising, licensing, and affiliate revenues that fund The Times’s ability to continue producing its current level of groundbreaking journalism,” it adds.

In response to the lawsuit, an OpenAI spokesperson said in a statement that the company respects “the rights of content creators and owners” and is “committed to working with them to ensure they benefit from AI technology and new revenue models.”

Brauneis said some of the “most impressive” portions of the Times case are its repeated examples of the AI models simply regurgitating its material, nearly verbatim.

Earlier copyright lawsuits haven’t been able to show such direct reproductions of their material by the models, Khan noted.

In recent months, courts have dismissed claims from plaintiffs in similar lawsuits who argued that the outputs of particular AI models infringed on their copyright because they failed to show outputs that were substantially similar to their copyrighted work.

“I think [the Times] did a good job relative to what maybe other complaints have been put out in the past,” Khan told The Hill. “They provided multiple examples of basically snippets and quite frankly more than snippets, passages of the New York Times as reproductions.”

Khan suggested the court could decide that particular use cases of generative AI are not transformative enough and require companies to limit certain prompts or outputs to prevent AI models from reproducing copyrighted content.

While Brauneis similarly noted the issue could result in an injunction against the tech companies or damages for the Times, he also emphasized it is not an unsolvable issue for generative AI.

“I think that the companies will respond to that and develop filters that dramatically reproduce and reduce the incidence of that kind of output,” he said. “So, I don’t think that’s a long-term, huge problem for these companies.”

In an October response to an inquiry from the U.S. Copyright Office, OpenAI said it had developed measures to reduce the likelihood of “memorization” or verbatim repetition by its AI models, including removing duplications from its training data and teaching its models to decline prompts aimed at reproducing copyrighted works.

The company noted, however, “Because of the multitude of ways a user may ask questions, ChatGPT may not be perfect at understanding and declining every request aimed at getting outputs that may include some part of content the model was trained on.”

The AI model is also equipped with output filters that can block potentially violative content that is generated despite other safeguards, OpenAI said.

OpenAI also emphasized in a statement on Monday that memorization is a “rare bug” and alleged that the Times “intentionally manipulated prompts” in order to get ChatGPT to regurgitate its articles.

“Even when using such prompts, our models don’t typically behave the way The New York Times insinuates, which suggests they either instructed the model to regurgitate or cherry-picked their examples from many attempts,” the company said.

“Despite their claims, this misuse is not typical or allowed user activity, and is not a substitute for The New York Times,” it added. “Regardless, we are continually making our systems more resistant to adversarial attacks to regurgitate training data, and have already made much progress in our recent models.”

How the media, AI can shape each other

Carl Szabo, the vice president and general counsel of the tech industry group NetChoice, warned that lawsuits like the Times’ could stifle the industry.

“You’re gonna see a bunch of these efforts to kind of shakedown AI developers for money in a way that harms the public, that harms public access to information and kind of undermines the purpose of the Copyright Act, which is to promote human knowledge at the end of the day,” Szabo told The Hill.

Eventually, Khan said he thinks there will be a mechanism in place through which tech companies can obtain licenses to content, such as articles from the Times, for training their AI models.

OpenAI has already struck deals with The Associated Press and Axel Springer — a German media company that owns Politico, Business Insider and other publications — to use their content.

The Times also noted in its lawsuit that it reached out to Microsoft and OpenAI in April to raise intellectual property concerns and the possibility of an agreement, which OpenAI acknowledged in its statement about the case.

“Our ongoing conversations with the New York Times have been productive and moving forward constructively, so we are surprised and disappointed with this development,” a spokesperson said.

The OpenAI spokesperson added that the company is “hopeful that we will find a mutually beneficial way to work together.”

“I think most publishers will adopt that model because it provides for additional revenue to the company,” Khan told The Hill. “And we can see that because New York Times tried to enter into [an agreement]. So, there is a price that they’re willing to accept.”

Technology, Business After a year of explosive growth, generative artificial intelligence (AI) may be facing its most significant legal threat yet from The New York Times. The Times sued Microsoft and OpenAI, the company behind the popular ChatGPT tool, for copyright infringement shortly before the new year, alleging the companies impermissibly used millions of its articles to…

Business

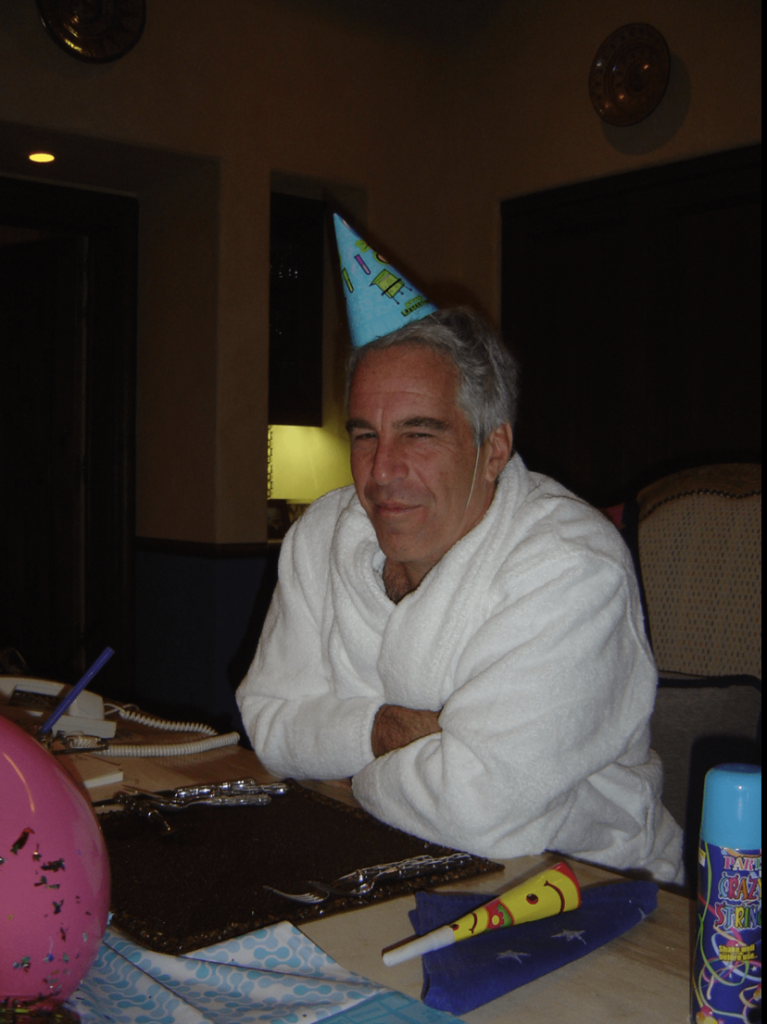

How Epstein’s Cash Shaped Artists, Agencies, and Algorithms

Jeffrey Epstein’s money did more than buy private jets and legal leverage. It flowed into the same ecosystem that decides which artists get pushed to the front, which research gets labeled “cutting edge,” and which stories about race and power are treated as respectable debate instead of hate speech. That doesn’t mean he sat in a control room programming playlists. It means his worldview seeped into institutions that already shape what we hear, see, and believe.

The Gatekeepers and Their Stains

The fallout around Casey Wasserman is a vivid example of how this works. Wasserman built a powerhouse talent and marketing agency that controls a major slice of sports, entertainment, and the global touring business. When the Epstein files revealed friendly, flirtatious exchanges between Wasserman and Ghislaine Maxwell, and documented his ties to Epstein’s circle, artists and staff began to question whose money and relationships were quietly underwriting their careers.

That doesn’t prove Epstein “created” any particular star. But it shows that a man deeply entangled with Epstein was sitting at a choke point: deciding which artists get representation, which tours get resources, which festivals and campaigns happen. In an industry built on access and favor, proximity to someone like Epstein is not just gossip; it signals which values are tolerated at the top.

When a gatekeeper with that history sits between artists and the public, “the industry” stops being an abstract machine and starts looking like a web of human choices — choices that, for years, were made in rooms where Epstein’s name wasn’t considered a disqualifier.

Funding Brains, Not Just Brands

Epstein’s interest in culture didn’t end with celebrity selfies. He was obsessed with the science of brains, intelligence, and behavior — and that’s where his money begins to overlap with how audiences are modeled and, eventually, how algorithms are trained.

He cultivated relationships with scientists at elite universities and funded research into genomics, cognition, and brain development. In one high‑profile case, a UCLA professor specializing in music and the brain corresponded with Epstein for years and accepted funding for an institute focused on how music affects neural circuits. On its face, that looks like straightforward philanthropy. Put it next to his email trail and a different pattern appears.

Epstein’s correspondence shows him pushing eugenics and “race science” again and again — arguing that genetic differences explain test score gaps between Black and white people, promoting the idea of editing human beings under the euphemism of “genetic altruism,” and surrounding himself with thinkers who entertained those frames. One researcher in his orbit described Black children as biologically better suited to running and hunting than to abstract thinking.

So you have a financier who is:

- Funding brain and behavior research.

- Deeply invested in ranking human groups by intelligence.

- Embedded in networks that shape both scientific agendas and cultural production.

None of that proves a specific piece of music research turned into a specific Spotify recommendation. But it does show how his ideology was given time, money, and legitimacy in the very spaces that define what counts as serious knowledge about human minds.

How Ideas Leak Into Algorithms

There is another layer that is easier to see: what enters the knowledge base that machines learn from.

Fringe researchers recently misused a large U.S. study of children’s genetics and brain development to publish papers claiming racial hierarchies in IQ and tying Black people’s economic outcomes to supposed genetic deficits. Those papers then showed up as sources in answers from large AI systems when users asked about race and intelligence. Even after mainstream scientists criticized the work, it had already entered both the academic record and the training data of systems that help generate and rank content.

Epstein did not write those specific papers, but he funded the kind of people and projects that keep race‑IQ discourse alive inside elite spaces. Once that thinking is in the mix, recommendation engines and search systems don’t have to be explicitly racist to reproduce it. They simply mirror what’s in their training data and what has been treated as “serious” research.

Zoomed out, the pipeline looks less like a neat conspiracy and more like an ecosystem:

- Wealthy men fund “edgy” work on genes, brains, and behavior.

- Some of that work revives old racist ideas with new data and jargon.

- Those studies get scraped, indexed, and sometimes amplified by AI systems.

- The same platforms host and boost music, video, and news — making decisions shaped by engagement patterns built on biased narratives.

The algorithm deciding what you see next is standing downstream from all of this.

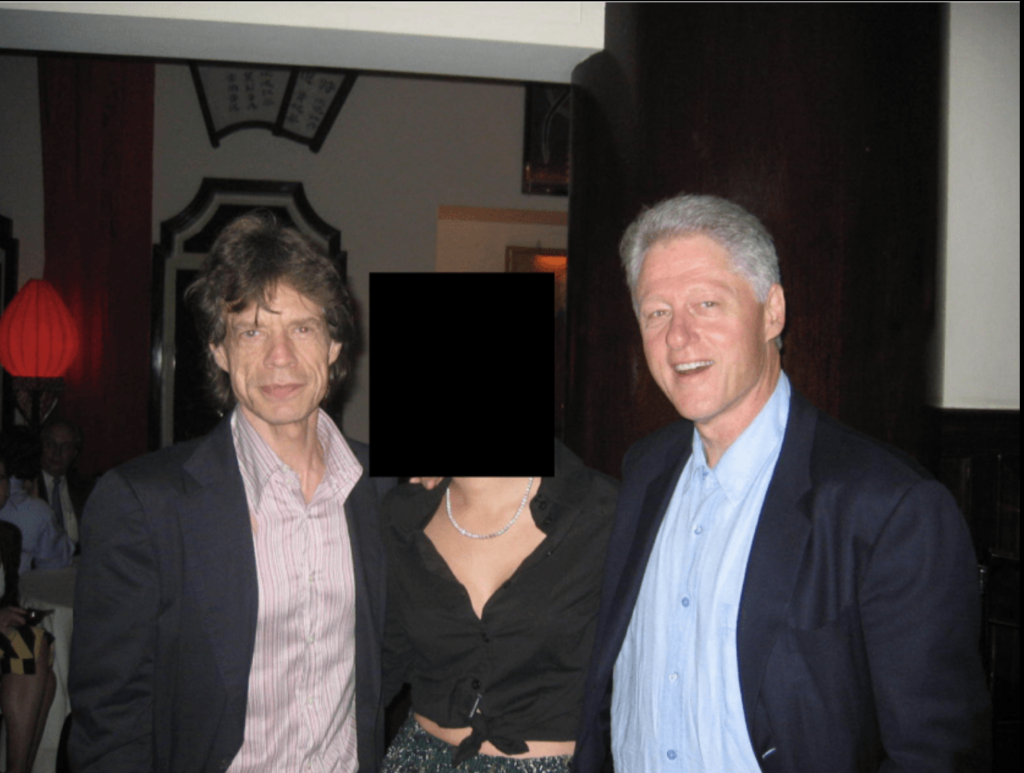

The Celebrity as Smoke Screen

Epstein’s contact lists are full of directors, actors, musicians, authors, and public intellectuals. Many now insist they had no idea what he was doing. Some probably didn’t; others clearly chose not to ask. From Epstein’s perspective, the value of those relationships is obvious.

Being seen in orbit around beloved artists and cultural figures created a reputational firewall. If the public repeatedly saw him photographed with geniuses, Oscar winners, and hit‑makers, their brains filed him under “eccentric patron” rather than “dangerous predator.”

That softens the landing for his ideas, too. Race science sounds less toxic when it’s discussed over dinner at a university‑backed salon or exchanged in emails with a famous thinker.

The more oxygen is spent on the celebrity angle — who flew on which plane, who sat at which dinner — the less attention is left for what may matter more in the long run: the way his money and ideology were welcomed by institutions that shape culture and knowledge.

What to Love, Who to Fear

The point is not to claim that Jeffrey Epstein was secretly programming your TikTok feed or hand‑picking your favorite rapper. The deeper question is what happens when a man with his worldview is allowed to invest in the people and institutions that decide:

- Which artists are “marketable.”

- Which scientific questions are “important.”

- Which studies are “serious” enough to train our machines on.

- Which faces and stories are framed as aspirational — and which as dangerous.

If your media diet feels saturated with certain kinds of Black representation — hyper‑visible in music and sports, under‑represented in positions of uncontested authority — while “objective” science quietly debates Black intelligence, that’s not random drift. It’s the outcome of centuries of narrative work that men like Epstein bought into and helped sustain.

No one can draw a straight, provable line from his bank account to a specific song or recommendation. But the lines he did draw — to elite agencies, to brain and music research, to race‑obsessed science networks — are enough to show this: his money was not only paying for crimes in private. It was also buying him a seat at the tables where culture and knowledge are made, where the stories about who to love and who to fear get quietly agreed upon.

A Challenge to Filmmakers and Creatives

For anyone making culture inside this system, that’s the uncomfortable part: this isn’t just a story about “them.” It’s also a story about you.

Filmmakers, showrunners, musicians, actors, and writers all sit at points where money, narrative, and visibility intersect. You rarely control where the capital ultimately comes from, but you do control what you validate, what you reproduce, and what you challenge.

Questions worth carrying into every room:

- Whose gaze are you serving when you pitch, cast, and cut?

- Which Black characters are being centered — and are they full humans or familiar stereotypes made safe for gatekeepers?

- When someone says a project is “too political,” “too niche,” or “bad for the algorithm,” whose comfort is really being protected?

- Are you treating “the industry” as a neutral force, or as a set of human choices you can push against?

If wealth like Epstein’s can quietly seep into agencies, labs, and institutions that decide what gets made and amplified, then the stories you choose to tell — and refuse to tell — become one of the few levers of resistance inside that machine. You may not control every funding source, but you can decide whether your work reinforces a world where Black people are data points and aesthetics, or one where they are subjects, authors, and owners.

The industry will always have its “gatekeepers.” The open question is whether creatives accept that role as fixed, or start behaving like counter‑programmers: naming the patterns, refusing easy archetypes, and building alternative pathways, platforms, and partnerships wherever possible. In a landscape where money has long been used to decide what to love and who to fear, your choices about whose stories get light are not just artistic decisions. They are acts of power.

Business

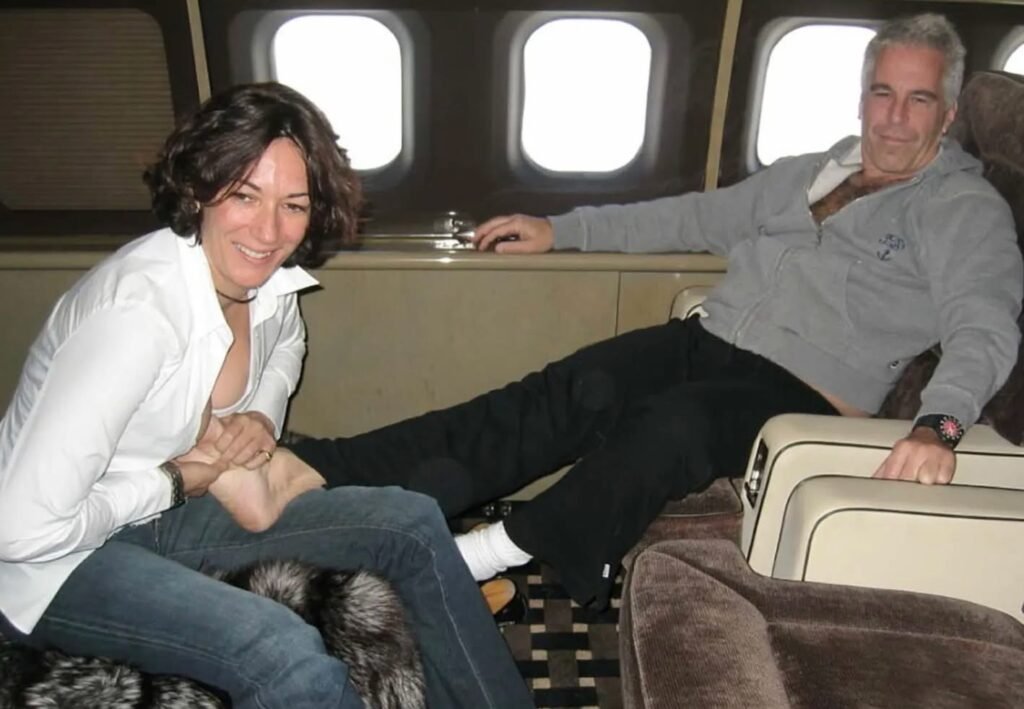

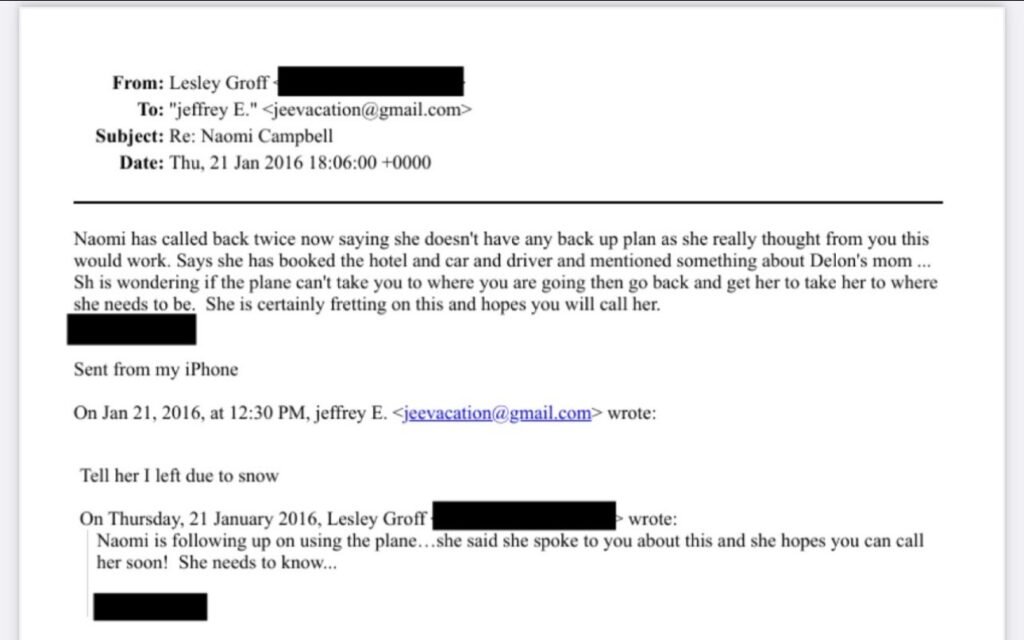

New DOJ Files Reveal Naomi Campbell’s Deep Ties to Jeffrey Epstein

In early 2026, the global conversation surrounding the “Epstein files” has reached a fever pitch as the Department of Justice continues to un-redact millions of pages of internal records. Among the most explosive revelations are detailed email exchanges between Ghislaine Maxwell and Jeffrey Epstein that directly name supermodel Naomi Campbell. While Campbell has long maintained she was a peripheral figure in Epstein’s world, the latest documents—including an explicit message where Maxwell allegedly offered “two playmates” for the model—have forced a national re-evaluation of her proximity to the criminal enterprise.

The Logistics of a High-Fashion Connection

The declassified files provide a rare look into the operational relationship between the supermodel and the financier. Flight logs and internal staff emails from as late as 2016 show that Campbell’s travel was frequently subsidized by Epstein’s private fleet. In one exchange, Epstein’s assistants discussed the urgency of her travel requests, noting she had “no backup plan” and was reliant on his jet to reach international events.

This level of logistical coordination suggests a relationship built on significant mutual favors, contrasting with Campbell’s previous descriptions of him as just another face in the crowd.

In Her Own Words: The “Sickened” Response

Campbell has not remained silent as these files have surfaced, though her defense has been consistent for years. In a widely cited 2019 video response that has been recirculated amid the 2026 leaks, she stated, “What he’s done is indefensible. I’m as sickened as everyone else is by it.” When confronted with photos of herself at parties alongside Epstein and Maxwell, she has argued against the concept of “guilt by association,” telling the press:

She has further emphasized her stance by aligning herself with those Epstein harmed, stating,

“I stand with the victims. I’m not a person who wants to see anyone abused, and I never have been.””

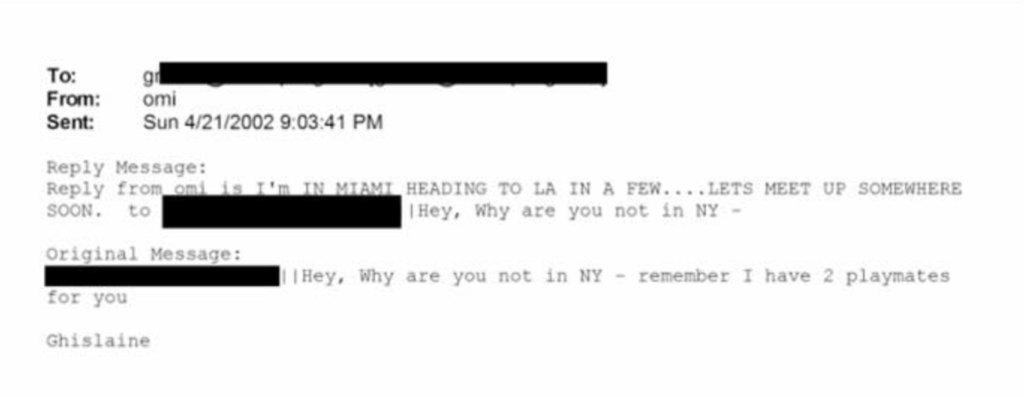

The Mystery of the “Two Playmates”

The most damaging piece of evidence in the recent 2026 release is an email where Maxwell reportedly tells Epstein she has “two playmates” ready for Campbell.

While the context of this “offer” remains a subject of intense debate—with some investigators suggesting it refers to the procurement of young women for social or sexual purposes—Campbell’s legal team has historically dismissed such claims as speculative. However, for a public already wary of elite power brokers, the specific wording used in these private DOJ records has created a “stop-the-scroll” moment that is proving difficult for the fashion icon to move past.

A Reputation at a Crossroads

As a trailblazer in the fashion industry, Campbell is now navigating a period where her professional achievements are being weighed against her presence in some of history’s most notorious social circles. The 2026 files don’t just name her; they place her within a broader system where modeling agents and scouts allegedly groomed young women under the guise of high-fashion opportunities. Whether these records prove a deeper complicity or simply illustrate the unavoidable overlap of the 1% remains the central question of the ongoing DOJ investigation.

Business

Google Accused Of Favoring White, Asian Staff As It Reaches $28 Million Deal That Excludes Black Workers

Google has tentatively agreed to a $28 million settlement in a California class‑action lawsuit alleging that white and Asian employees were routinely paid more and placed on faster career tracks than colleagues from other racial and ethnic backgrounds.

- A Santa Clara County Superior Court judge has granted preliminary approval, calling the deal “fair” and noting that it could cover more than 6,600 current and former Google workers employed in the state between 2018 and 2024.

How The Discrimination Claims Emerged

The lawsuit was brought by former Google employee Ana Cantu, who identifies as Mexican and racially Indigenous and worked in people operations and cloud departments for about seven years. Cantu alleges that despite strong performance, she remained stuck at the same level while white and Asian colleagues doing similar work received higher pay, higher “levels,” and more frequent promotions.

Cantu’s complaint claims that Latino, Indigenous, Native American, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and Alaska Native employees were systematically underpaid compared with white and Asian coworkers performing substantially similar roles. The suit also says employees who raised concerns about pay and leveling saw raises and promotions withheld, reinforcing what plaintiffs describe as a two‑tiered system inside the company.

Why Black Employees Were Left Out

Cantu’s legal team ultimately agreed to narrow the class to employees whose race and ethnicity were “most closely aligned” with hers, a condition that cleared the path to the current settlement.

The judge noted that Black employees were explicitly excluded from the settlement class after negotiations, meaning they will not share in the $28 million payout even though they were named in earlier versions of the case. Separate litigation on behalf of Black Google employees alleging racial bias in pay and promotions remains pending, leaving their claims to be resolved in a different forum.

What The Settlement Provides

Of the $28 million total, about $20.4 million is expected to be distributed to eligible class members after legal fees and penalties are deducted. Eligible workers include those in California who self‑identified as Hispanic, Latinx, Indigenous, Native American, American Indian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and/or Alaska Native during the covered period.

Beyond cash payments, Google has also agreed to take steps aimed at addressing the alleged disparities, including reviewing pay and leveling practices for racial and ethnic gaps. The settlement still needs final court approval at a hearing scheduled for later this year, and affected employees will have a chance to opt out or object before any money is distributed.

H2: Google’s Response And The Broader Stakes

A Google spokesperson has said the company disputes the allegations but chose to settle in order to move forward, while reiterating its public commitment to fair pay, hiring, and advancement for all employees. The company has emphasized ongoing internal audits and equity initiatives, though plaintiffs argue those efforts did not prevent or correct the disparities outlined in the lawsuit.

For many observers, the exclusion of Black workers from the settlement highlights the legal and strategic complexities of class‑action discrimination cases, especially in large, diverse workplaces. The outcome of the remaining lawsuit brought on behalf of Black employees, alongside this $28 million deal, will help define how one of the world’s most powerful tech companies is held accountable for alleged racial inequities in pay and promotion.

Advice7 days ago

Advice7 days agoHow to Make Your Indie Film Pay Off Without Losing Half to Distributors

Entertainment4 weeks ago

Entertainment4 weeks agoWhat the Epstein Files Actually Say About Jay-Z

Film Industry4 weeks ago

Film Industry4 weeks agoAI Didn’t Steal Your Job. It Revealed Who Actually Does the Work.

Entertainment3 weeks ago

Entertainment3 weeks agoWhat Epstein’s Guest Lists Mean for Working Filmmakers: Who Do You Stand Next To?

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoHow Epstein’s Cash Shaped Artists, Agencies, and Algorithms

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoCatherine O’Hara: The Comedy Genius Who Taught Us That Character Is Everything

Film Industry7 days ago

Film Industry7 days agoWhy Burnt-Out Filmmakers Need to Unplug Right Now

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoNew DOJ Files Reveal Naomi Campbell’s Deep Ties to Jeffrey Epstein