Film Industry

How to Sell Indie Movies and Get Minimum Guarantees

For independent filmmakers, few experiences are more discouraging than spending two years creating a film — investing significant time, energy, and money — only to see it make little or no revenue and receive minimal viewership.

This not only impacts morale but also makes it difficult to reinvest profits into the next project. Without revenue from a previous film, filmmakers often need to return to unrelated jobs or go through lengthy funding processes before they can start production again.

However, securing minimum guarantees (MGs) from distributors is still possible today — despite the widespread belief that it’s no longer achievable. Here’s how filmmakers can make it happen.

The Harsh Reality of Indie Film Distribution

Why Many Filmmakers Never See a Profit

Working with a sales agent (who typically takes 15–20%) and a distributor (another 20–35%) often means giving away roughly half of a film’s revenue before any profit is seen.

Additionally, marketing caps — ranging from $3,000 to $15,000 — are deducted from sales before any payouts. Coupled with non-transparent accounting and questionable business practices from some companies, many independent filmmakers end up with nothing.

The Limited Reach of Sales Agents

Even reputable sales agents sometimes submit a film to as few as 25 distributors worldwide. This drastically limits opportunities. Furthermore, agents often push for worldwide rights deals, which can be less profitable than selling rights territory-by-territory.

Why Filmmakers Should Consider Acting as Their Own Sales Agent

By managing sales themselves, filmmakers can:

- Directly contact hundreds of distributors

- Negotiate deals without middlemen

- Pursue territory-specific rights sales for stronger returns

Some filmmakers who’ve adopted this approach built contact lists of hundreds of distributors — reaching out to over 200 companies per film — and achieved 15 to 20 offers, including multiple MGs, even without A-list talent.

The Power of Outreach Volume

Why Numbers Matter

- Typical sales agent approach: 25 contacts → maybe 1 deal.

- Direct outreach approach: 225+ contacts → 15–20 offers.

A larger pool of potential buyers increases the likelihood of attracting the right match. Importantly, a film doesn’t have to appeal to every distributor — just a select few who are willing to commit.

Steps to Selling a Film Independently

Step 1 – Build a Distributor Contact List

Research every possible legitimate company in every market. A comprehensive list may take hundreds of hours to build.

Step 2 – Craft a Clear & Concise Pitch

Include in the email:

- Confirmation that the film is complete

- Cast list (plus notable social media followings if applicable)

- Genre (critical for most buyers)

- A logline (one-sentence synopsis)

- Trailer link (~90 seconds)

- A line offering to share the full feature upon request

Step 3 – Sell by Territory, Not Worldwide

Selling rights territory-by-territory can yield more MGs, more diverse revenue streams, and reduce reliance on a single distributor.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Choosing a “name” distributor purely for prestige — Unless it’s a major platform like Netflix, the name alone rarely impacts career growth or revenue.

- Relying on one distributor — Spreading sales across 10–15 distributors reduces risk and increases reach.

- Ignoring foreign markets — Countries like Germany, Italy, Japan, and the UK can offer excellent returns for specific films.

Alternatives if Strong Offers Don’t Arrive

If no attractive MGs are secured, self-distribution becomes a viable backup. Aggregators enable filmmakers to release on platforms like Amazon and Apple TV/iTunes without a traditional distributor. Although some premium services like Hulu may still require partnerships, independent release keeps profits and control in the filmmaker’s hands.

The Bottom Line

To succeed in today’s market, filmmakers must think like entrepreneurs. Rather than depending entirely on traditional sales agents and distributors, controlling the sales process can open more opportunities, secure more MGs, and ensure films are seen in multiple regions with multiple partners promoting them.

Film Industry

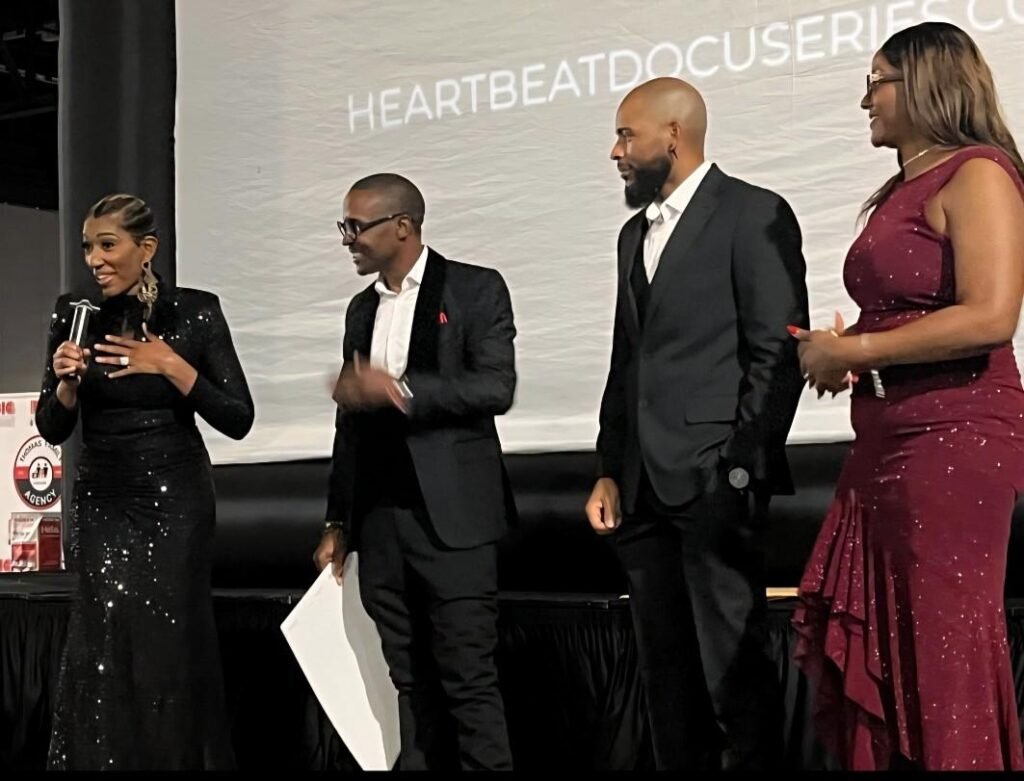

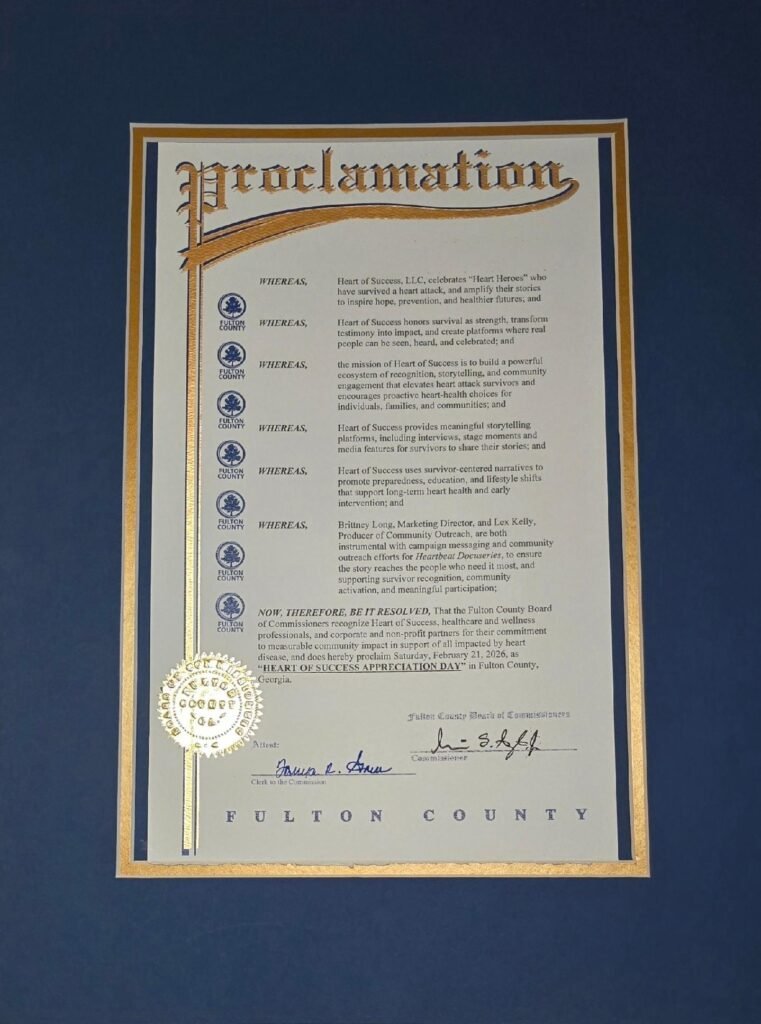

Dr. Ric Mathis Turns a Film Screening Into a Lifesaving Movement With Heartbeat

One person dies every 34 seconds from cardiovascular disease in the United States. That statistic opened the evening—and by the time the lights came back on, it had changed the way an entire room thought about their own.

Dr. Ric Mathis, the internationally recognized filmmaker known as the “Documentary King,” brought his latest docuseries Heartbeat to a packed screening event that was equal parts cinema, community gathering, and public health intervention. What unfolded was more than a premiere—it was a moment that could genuinely save lives.

A Silent Killer Meets a Powerful Storyteller

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States, killing more Americans than all forms of cancer and accidental deaths combined. In 2022 alone, cardiovascular disease claimed about 941,652 lives nationwide. Yet for all its devastation, heart disease often arrives without warning: in the U.S., someone has a heart attack every 40 seconds, and about 1 in 5 of those heart attacks is “silent” — the damage is done, but the person doesn’t even know it.

That invisible danger is exactly what Heartbeat confronts head-on. From the opening seconds of the trailer—“I didn’t even see this thing coming. It was silent. It was sudden. And for many of us… it’s deadly.”—the audience is pulled into the harrowing, first-person accounts of survivors who came within moments of losing everything. One survivor describes their actual heart being placed on ice while their fate hung in the balance. The silence in the room says it all: this is no longer a statistic on a screen; it is a mirror.

The Numbers That Shook the Room

Dr. Mathis doesn’t just tell a story—he arms his audience with facts that demand action:

- In the United States, someone has a heart attack every 40 seconds.newsroom.heart+1

- Roughly 805,000 heart attacks occur in the U.S. each year; 605,000 of them are first-time events.

- More than 350,000 people experience cardiac arrest outside a hospital annually, and only about 10% survive, even with paramedic treatment.

- Cardiovascular disease costs the U.S. an estimated hundreds of billions of dollars in direct and indirect costs every year.

These numbers land differently when paired with the faces and voices in the documentary. Attendees described seeing their parents, their partners, and even themselves in the stories on screen.

A Wake-Up Call for Black Communities

The screening carries particular weight for the Black community, where the stakes are even higher.

Black Americans are about 30% more likely to die from heart disease than white Americans.

Black men face a significantly higher risk of developing heart failure compared with white men. African Americans also have some of the highest rates of uncontrolled hypertension in the world, dramatically increasing their risk of heart disease and stroke.

A major Tulane University study found that Black Americans are 54% more likely to die from cardiovascular disease, and that this disparity is driven largely by social determinants of health such as unemployment, low income, food insecurity, and lack of access to care. When researchers adjusted for these social factors, the racial gap in cardiovascular deaths completely disappeared.

This is the injustice Heartbeat refuses to let audiences ignore. Dr. Mathis uses the post-screening conversation to connect the dots between systemic inequality and the heart attacks happening in neighborhoods across the country—turning grief into understanding, and understanding into action.

From Screening Room to Doctor’s Office

What sets this event apart is how Dr. Mathis blends powerful storytelling with real-world solutions. Following the film, he leads a candid panel discussion with medical professionals and heart attack survivors, covering symptoms, prevention strategies, and often-overlooked warning signs—especially in communities where trust in healthcare has been historically broken.

The results are immediate and tangible:

- Guests sign up for health screenings on the spot.

- Attendees pledge to schedule overdue medical appointments.

- Clips and quotes from the film flood social media, turning one screening into a living awareness campaign.

- Multiple guests say the film “might have just saved my life.”

- Others commit to sharing Heartbeat with their families, churches, and community organizations.

As many cardiologists note, too many patients—particularly Black patients—see a heart specialist only after they’ve had a cardiac event. Heartbeat is designed to reverse that pattern by making prevention feel urgent and personal.

More Than a Film—A Movement

Dr. Ric Mathis has spent more than two decades using the screen as a tool for empowerment—from his acclaimed Black Friday documentary series to the biographical film Bo Legs and his financial literacy work through Rich Kid Society. With Heartbeat, he has extended that mission into the most intimate territory yet: keeping people alive.

The success of this screening is not measured in ticket sales alone. It is measured in the quiet decisions people make afterward—to get checked, to change a habit, to have a difficult conversation about health, to stop ignoring warning signs. In a country where heart disease is responsible for roughly 1 in every 3 deaths, and where the first symptom can sometimes be the last, awareness is not optional—it is survival.

If even one life is saved because someone sat in that theater and decided to take action, then Heartbeat has done exactly what it was created to do.

Entertainment

When “Professional” Means Silent

Michael B. Jordan and Delroy Lindo did not walk onto the BAFTA stage expecting to become a case study in how the industry mishandles racism in real time. They were there to present, hit their marks, and do what award shows have always asked of Black talent: bring charisma, sell the moment, keep the night moving.

Instead, while they stood under the lights, a man in the audience shouted the N‑word. The word carried across the theater and through the broadcast. The cameras kept rolling. The teleprompter kept scrolling. And the two men at the center of it did what they’ve been trained their entire careers to do: they kept going.

The incident was shocking, but the pattern around it was familiar.

The Apologies That Came After the Credits

In the days that followed, BAFTA released a public apology. The organization said it took responsibility for putting its guests “in a very difficult situation,” acknowledged that the word used carries deep trauma, and apologized to Michael B. Jordan and Delroy Lindo. It also praised them for their “dignity and professionalism” in continuing to present.

The man who shouted the slur, a Tourette syndrome campaigner, explained that his outbursts are involuntary and expressed remorse for the pain his tic caused. That context about disability matters. Any honest conversation has to hold space for the reality that not every harmful word is spoken with intent.

But context doesn’t erase impact. For people watching at home—and especially for the men on that stage—the sequence was still the same: a slur detonated in the room, the show continued as if nothing happened, and the institutional response arrived later, in carefully crafted language.

Delroy Lindo summed up the experience by saying he and Jordan “did what we had to do,” and added that he wished someone from the organization had spoken with them directly afterward. That gap between polished statements and real‑time care is exactly where trust breaks down.

Who Is “Professionalism” Really Protecting?

Strip away the PR and a hard truth emerges: almost all of the pressure fell on the people who were harmed, not the people in charge.

On stage, “professionalism” meant Jordan and Lindo were expected to stay composed so the room wouldn’t be uncomfortable. Off stage, “professionalism” meant the institution focused on managing optics after the fact instead of disrupting the show in the moment.

That raises a question the industry rarely wants to confront:

When we call for professionalism, whose comfort are we protecting?

For Black artists, professionalism has too often meant:

- Take the hit and keep your face neutral.

- Don’t make it awkward for the audience or the brand.

- Don’t risk being labeled “difficult,” no matter how blatant the disrespect.

It’s easy to admire that composure. It’s harder to admit that the system routinely demands it from the very people absorbing the harm.

If It Can Happen There, It Can Happen Anywhere

This didn’t happen in a chaotic open mic or an unsupervised live stream. It happened at one of the most carefully produced film ceremonies in the world—an event with run‑of‑show documents, stage managers, and communication channels in everyone’s ears.

If an incident like this can unfold there without a pause, it can unfold anywhere:

- At a regional festival Q&A when an audience member crosses a line.

- At a comedy show when someone heckles with a “joke” that’s really just a slur.

- At a film panel where the only Black creator on stage gets a loaded question and is expected to smile through it.

The honest question for anyone who runs events isn’t “How could BAFTA let this happen?” It’s “What would we actually do if it happened in our room?”

Would your moderator know they have explicit permission to stop everything?

Would your team know who goes to the stage, who speaks to the audience, and who stays with the person targeted?

Or would you also be scrambling to get the language right in a statement tomorrow?

Redefining Professionalism in 2026

If this moment is going to mean anything, the definition of professionalism has to change.

Professionalism cannot just be “don’t lose your cool on stage.” It has to include the courage and structure to protect the people on that stage when something goes wrong.

A better standard looks like this:

- Pause the show when serious harm happens. A clean program is not more important than a person’s dignity.

- Acknowledge it in the room. Name what happened in clear terms instead of pretending it didn’t occur and quietly editing it later.

- Center the person targeted. Check on them, give them options, and let their comfort—not the schedule—drive the next move.

- Plan the response before you need it. Build safety and harassment protocols into your festival, awards show, or live event so no one is improvising under pressure.

Sometimes the most professional thing you can do is allow a little discomfort in the room. It signals that human beings matter more than the illusion of seamlessness.

The Standard Going Forward

Michael B. Jordan and Delroy Lindo did what they have always been rewarded for doing: they protected the show. They shouldn’t have had to.

True respect for their craft and humanity would have looked like a room that moved to protect them instead—stopping the script, resetting the energy, and making it clear that the problem wasn’t their reaction, but the harm they’d just absorbed.

No performer should be asked to choose between their dignity and their career. So if you work anywhere in this industry—onstage or behind the scenes—this incident quietly handed you a new baseline:

Call it out.

Pause the show.

Back the person who was harmed.

That’s what professionalism should mean in 2026.

Film Industry

Why Burnt-Out Filmmakers Need to Unplug Right Now

If you’re reading this at 2 AM, scrolling through industry news instead of writing your script, you already know something’s wrong.

You’re not lazy. You’re not untalented. You’re burnt out—and you’re far from alone.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

87% of film and TV workers are facing mental health challenges right now. 62% of creators report burnout, with 65% constantly obsessing over content performance. Even more alarming: 1 in 10 creators experience suicidal thoughts—nearly twice the rate of the general population.

But here’s what the statistics don’t capture: the paralysis. The endless scrolling. The “should I make a feature or pivot to vertical shorts?” loop that keeps you stuck for months. The guilt of watching tutorials instead of shooting. The way political chaos and industry upheaval make creating feel pointless.

The Trap You’re In

You’re waiting. Waiting for the algorithm to make sense. Waiting for the industry to be “fair” again. Waiting for the perfect format, the right budget, the ideal moment when your head is finally clear enough to make something worthy.

That moment isn’t coming.

The filmmakers you admire didn’t wait for perfect conditions. They made their breakthrough films during recessions, pandemics, personal crises, and industry chaos. The only difference between them and you right now? They gave themselves permission to create imperfectly.

Why Now Is Actually the Perfect Time

The industry’s chaos is real, but it’s also created an opening. Streaming platforms are hungry for authentic stories. Independent films are driving growth in the global film market. In 2026, filmmakers with deep trust in a niche have more power than studios chasing mass appeal.

But none of that matters if you’re too exhausted to pick up a camera.

The 3-Day Reset

Here’s what actually helps when you’re stuck:

Day 1: News blackout during creative hours. Not forever. Just when you’re supposed to be creating. The world will still be chaotic tomorrow—but you’ll have protected the only hours that matter for your art.

Day 2: Pick one format. Just one. Feature, shorts, or vertical content—it doesn’t matter which. What matters is ending the analysis paralysis. Your first project won’t be your breakthrough anyway. It’ll be your fifth. So start.

Day 3: Make something imperfect this week. Not good. Not portfolio-worthy. Just made. A 60-second test. A rough scene. Anything that reminds you why you started doing this in the first place.

The Real Problem Isn’t Your Idea

You don’t have a creativity problem. You have an input-overload problem. Your brain is processing election cycles, algorithm changes, industry layoffs, and the constant pressure to “choose the right path” before you’re “allowed” to create.

But creativity doesn’t work on permission slips.

72% of film and TV professionals say the industry is not a mentally healthy place to work. 59% struggle to maintain any work-life balance. 50% face relentless, unrealistic timelines. The system is designed to burn you out.

Your response can’t be to wait for the system to fix itself. It has to be to protect your creative energy like it’s the most valuable resource you have—because it is.

What Happens If You Don’t Reset

The filmmakers who “wait for the right time” never make their films. They become the people who talk about the script they’re “working on” for five years. They’re the ones who know every piece of gear, every distribution strategy, every festival deadline—but have nothing to submit.

Don’t let information replace creation. Don’t let the news cycle steal your narrative.

Start Monday

Not when things calm down. Not when you figure out the perfect format. Not when the industry is “fair” again.

Monday. Imperfectly. With whatever you have.

Your story—messy, unpolished, and made anyway—is what the world needs right now. Not your perfectly researched plan. Not your anxiety about choosing wrong.

Your work.

The filmmakers who win in 2026 won’t be the ones who waited for permission. They’ll be the ones who created despite the noise, shipped despite the doubt, and remembered that done beats perfect every single time.

So take the weekend. Unplug from the chaos. Rest without guilt.

Then Monday morning, make something imperfect.

The industry doesn’t need you to wait until you’re ready. It needs you to start before you feel ready—and figure it out as you go.

That’s not reckless. That’s how every film you’ve ever loved actually got made.

If this hit home, you’re not alone. Thousands of independent filmmakers are choosing to create despite the overwhelm. Start your 3-day reset Monday. Your future self will thank you.

Advice7 days ago

Advice7 days agoHow to Make Your Indie Film Pay Off Without Losing Half to Distributors

Entertainment4 weeks ago

Entertainment4 weeks agoWhat the Epstein Files Actually Say About Jay-Z

Film Industry4 weeks ago

Film Industry4 weeks agoAI Didn’t Steal Your Job. It Revealed Who Actually Does the Work.

Entertainment3 weeks ago

Entertainment3 weeks agoWhat Epstein’s Guest Lists Mean for Working Filmmakers: Who Do You Stand Next To?

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoHow Epstein’s Cash Shaped Artists, Agencies, and Algorithms

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoCatherine O’Hara: The Comedy Genius Who Taught Us That Character Is Everything

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoNew DOJ Files Reveal Naomi Campbell’s Deep Ties to Jeffrey Epstein

Film Industry7 days ago

Film Industry7 days agoWhy Burnt-Out Filmmakers Need to Unplug Right Now