Business

Experts thought they knew how the economy worked. After the pandemic, they’re not so sure. on December 7, 2023 at 11:00 am Business News | The Hill

The American economy, while never simple, was at least somewhat understood — until the pandemic upended even the most basic assumptions, experts told The Hill this week.

From the recession that didn’t happen, to the relationship between unemployment and inflation, to the reason that inflation took off in the first place, to the disconnect between national economic performance and people’s experience of it, to the efficacy of interest rate hikes — American economics and the people who follow it are having an identity crisis.

It’s not clear how it’s going to resolve.

Some economists feel vindicated by what they’ve seen play out, while others have changed their positions. Others have suggested entirely new models are needed and have encountered pushback from colleagues on that suggestion as well.

But no matter how you frame it, it’s undeniable that where there once was confidence, now a fretful mood has descended over a discipline trying to reconcile long-held dogmas with the near-wartime economic conditions brought on by the pandemic and the sensational recovery that followed.

“What you have is a shake-up of economics here in the United States, because we’re having a shift again,” Richard Wolff, emeritus professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a visiting professor at the New School, told The Hill.

“It remains to be seen in this episode to what extent the normal relationships of many, many kinds — labor, spending, inflation and others — will go back to their pre-pandemic norms, or will be permanently perturbed,” former Federal Reserve Vice Chairman Alan Blinder, a Princeton University economist, told The Hill.

Blinder, who oversaw a period of quantitative tightening in the mid-1990s during the Clinton administration, said the very efficacy of monetary policy is now up for debate.

A quasi-wartime economy plays by different rules

Economists see the end of World War II, when debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratios were about as high as where they are today and inflation was above 10 percent, as a point of comparison for the economy of today.

“The only real precedent that I can identify to the pandemic-era exertion of state control over the economy would be the two world wars,” Daniel Sargent, a professor of the history of public policy at the University of California, told The Hill in an interview.

“It’s also significant that some of the statutory authority that the federal government leaned upon in order to exercise the degree of control that it did derived from [the] Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917,” Sargent added.

While the economy of the 1970s also experienced a series of state interventions, including price controls as part of the “Nixon shock” intended to resolve inflation, the deficit spending of the pandemic makes the post-World War II period the most relevant analogue for today’s economy, Sargent said.

The sudden switch to such a high level of state intervention is likely a central reason that many traditional assumptions have broken down.

The comparison to the post-WWII period was also top of mind for Harvard University economist Stephen Marglin.

“During the pandemic, the same thing happened [as during the war]. There weren’t the civilian goods being produced, and people did get money, but they couldn’t spend it because the economy was shut down, just like the civilian economy had been shut down during WWII. That’s the analogy,” he told The Hill.

Marglin said that a doctrinal shift within economics akin to those that reshaped the discipline in the 1930s and again in the 1970s “probably should happen” but that he wasn’t seeing any immediate signs of a major course correction.

Causes of inflation spark debate but unite major thinkers

While the nation’s current battle with inflation has sparked a small industry of rhetorical debate, many experts The Hill spoke to said there’s an implicit agreement among different camps that stitches the different arguments together.

Republicans and conservative economists tend to argue that inflation was caused primarily by the trillions in deficit spending the government sent out to bolster households and businesses during lockdowns.

Democrats and liberal economists focus on muddled supply chains and even corporate greed as the primary drivers.

But the private-sector response to the public-sector spending spans both these explanations, economists say.

“What we had was a situation in which corporations across America understood that the money pumped into the economy to cope with the crash that we were due to have, coupled with the pandemic, was an extraordinary time. The government pumped in enormous amounts of money, enormous amounts of fiscal stimulus, and this made it possible to raise prices to improve profitability,” the New School’s Richard Wolff said.

While the cash injection into the economy made it possible for companies to raise their prices, it also allowed people to keep spending money, helping to stave off recession.

“The central view, I feel, is totally vindicated,” Hoover Institution economist and former University of Chicago finance professor John Cochrane told The Hill. “The central reason we got inflation is the government printed up about $3 trillion and borrowed another $2 trillion, and sent people checks.”

“That’s also consistent with why inflation eased, even without the Fed really doing anything,” he added. “It did not repeat 1980 to 1982 when interest rates were well below inflation even after the Fed started raising them. A one time fiscal blowout raises the price level, so you get a burst of inflation that eventually goes away.”

So why haven’t we seen a recession?

“A US recession is effectively certain in the next 12 months,” Bloomberg News reported in October of last year, citing its own economic model.

“The latest recession probability models by Bloomberg economists … forecast a higher recession probability across all timeframes, with the 12-month estimate of a downturn by October 2023 hitting 100 percent,” the economists found — erroneously.

Some big-time financial players got swept up in the groupthink on recession.

Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan predicted a “mild recession” in 2023, and JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon said a “hurricane” was forming over the economy.

Even the Federal Reserve predicted a “mild recession” in March before pulling that call later in the year.

Those economists could be forgiven for their confusion: Usually, after a central bank raises interest rates by more than 500 basis points, which makes financing more expensive for both businesses and consumers, the economy slows down.

Not so in 2023. Quarterly GDP growth has exceeded 2 percent for the last five quarters, rising as high as 5.2 percent annualized in the third quarter. Corporate profits have been through the roof.

Princeton’s Alan Blinder said the channels by which the Fed slowed the economy in the mid-1990s seem to have dried up during the current cycle.

“I can tell you for sure, though we didn’t relish enunciating this, that what we thought we were doing is slowing the economy down by putting the squeeze on the auto industry and housing. Neither of those channels seem very much to have worked this time,” he said.

Dean Baker, an economist with the Center for Economic Policy and Research, told The Hill much the same thing.

“It didn’t work through the usual channels,” he said, specifically citing new housing starts, which were relatively unresponsive to Fed rate hikes, as well as an unexpectedly strong performance of net exports.

Severed links between employment, inflation and interest rates

Perhaps the most central relationships that have been thrown into doubt are those between the rate of inflation, the level of interest rates and the level of employment.

Higher and rising prices are correlated through labor costs with higher levels of employment. And higher interest rates, which squeeze the economy, are associated with lower employment and therefore lower prices.

But as the Fed raised rates, and the annual inflation rate descended from 9 percent to just above 3 percent over the past year and a half, unemployment stayed below 4 percent the whole time. This breaks the rule.

“[Rate hikes] didn’t have the effect that just about any of us expected. If you told me the Fed was going to raise rates to 5.25 percent and the unemployment rate was going to remain under 4 percent, I wouldn’t have believed you,” Baker told The Hill.

Does Wall Street reflect America’s real economy anymore?

Surging profitability within the economy, which reached its highest level after the pandemic since the 1920s as a share of gross domestic income, has done little to raise the public’s economic mood.

Profits from current production increased $105.7 billion in the third quarter, compared with an increase of $6.9 billion in the second quarter, Commerce Department data released last week shows.

About 58 percent of Americans own stock in Wall Street companies, according to the Fed’s latest survey of consumer finances.

But that ownership is overwhelmingly skewed toward the extremely rich. In fact, the 99th to 100th percentile of richest households own the majority of all corporate equities in the U.S., a distribution that took off after the pandemic and is near a record high.

While the top 1 percent owns more than half of the stock market, the bottom 50 percent owns less than 1 percent of it.

That may be why just 19 percent of U.S. adults rate economic conditions as excellent or good “while 46 percent say conditions are only fair and 35 percent rate the economy as poor,” as public opinion researchers at Pew found earlier this year.

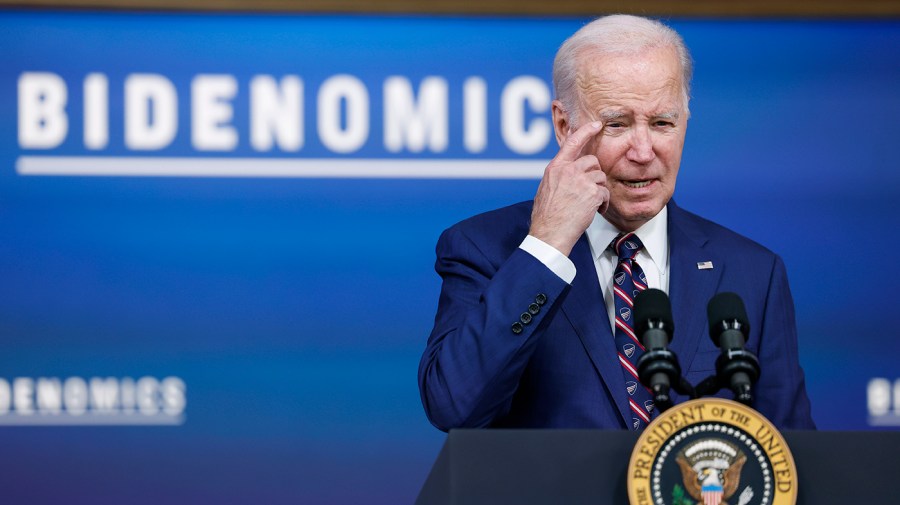

Despite many ostensibly excellent metrics spanning employment, GDP and decelerating inflation, public approval of President Biden’s economic stewardship is low. Only 32 percent of Americans think Biden is doing a good job with the economy, according to Gallup.

While wage growth has just about kept pace with price growth over the pandemic, longer-term trends in income distribution are almost certainly adding to Americans’ melancholy.

While the profit share of the economy hit 8.5 percent in 2022 and has been generally rising since around 1990, the share of the economy devoted to paying workers has fallen dramatically since 1970, dropping from about 51.6 percent on national income to 43.1 percent now.

“We really do need additional tools for combatting supply chain issues and excess demand. The reliance on this one sledgehammer of Federal Reserve interest policy is not very good,” Harvard’s Marglin told The Hill.

Traditional divisions between monetary policy, which is handled mainly by the Fed, and fiscal policy, which is handled by Congress, mean that even while the field of economics may be going through a period of change, policymakers may have limited tools to turn those changes into reality.

Administration, Business, International, News, Policy, corporate profits, economics, inflation, Interest rates, unemployment, US economy, Wages The American economy, while never simple, was at least somewhat understood — until the pandemic upended even the most basic assumptions, experts told The Hill this week. From the recession that didn’t happen, to the relationship between unemployment and inflation, to the reason that inflation took off in the first place, to the disconnect between…

Business

Google Accused Of Favoring White, Asian Staff As It Reaches $28 Million Deal That Excludes Black Workers

Google has tentatively agreed to a $28 million settlement in a California class‑action lawsuit alleging that white and Asian employees were routinely paid more and placed on faster career tracks than colleagues from other racial and ethnic backgrounds.

- A Santa Clara County Superior Court judge has granted preliminary approval, calling the deal “fair” and noting that it could cover more than 6,600 current and former Google workers employed in the state between 2018 and 2024.

How The Discrimination Claims Emerged

The lawsuit was brought by former Google employee Ana Cantu, who identifies as Mexican and racially Indigenous and worked in people operations and cloud departments for about seven years. Cantu alleges that despite strong performance, she remained stuck at the same level while white and Asian colleagues doing similar work received higher pay, higher “levels,” and more frequent promotions.

Cantu’s complaint claims that Latino, Indigenous, Native American, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and Alaska Native employees were systematically underpaid compared with white and Asian coworkers performing substantially similar roles. The suit also says employees who raised concerns about pay and leveling saw raises and promotions withheld, reinforcing what plaintiffs describe as a two‑tiered system inside the company.

Why Black Employees Were Left Out

Cantu’s legal team ultimately agreed to narrow the class to employees whose race and ethnicity were “most closely aligned” with hers, a condition that cleared the path to the current settlement.

The judge noted that Black employees were explicitly excluded from the settlement class after negotiations, meaning they will not share in the $28 million payout even though they were named in earlier versions of the case. Separate litigation on behalf of Black Google employees alleging racial bias in pay and promotions remains pending, leaving their claims to be resolved in a different forum.

What The Settlement Provides

Of the $28 million total, about $20.4 million is expected to be distributed to eligible class members after legal fees and penalties are deducted. Eligible workers include those in California who self‑identified as Hispanic, Latinx, Indigenous, Native American, American Indian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and/or Alaska Native during the covered period.

Beyond cash payments, Google has also agreed to take steps aimed at addressing the alleged disparities, including reviewing pay and leveling practices for racial and ethnic gaps. The settlement still needs final court approval at a hearing scheduled for later this year, and affected employees will have a chance to opt out or object before any money is distributed.

H2: Google’s Response And The Broader Stakes

A Google spokesperson has said the company disputes the allegations but chose to settle in order to move forward, while reiterating its public commitment to fair pay, hiring, and advancement for all employees. The company has emphasized ongoing internal audits and equity initiatives, though plaintiffs argue those efforts did not prevent or correct the disparities outlined in the lawsuit.

For many observers, the exclusion of Black workers from the settlement highlights the legal and strategic complexities of class‑action discrimination cases, especially in large, diverse workplaces. The outcome of the remaining lawsuit brought on behalf of Black employees, alongside this $28 million deal, will help define how one of the world’s most powerful tech companies is held accountable for alleged racial inequities in pay and promotion.

Business

Luana Lopes Lara: How a 29‑Year‑Old Became the Youngest Self‑Made Woman Billionaire

At just 29, Luana Lopes Lara has taken a title that usually belongs to pop stars and consumer‑app founders.

Multiple business outlets now recognize her as the world’s youngest self‑made woman billionaire, after her company Kalshi hit an 11 billion dollar valuation in a new funding round.

That round, a 1 billion dollar Series E led by Paradigm with Sequoia Capital, Andreessen Horowitz, CapitalG and others participating, instantly pushed both co‑founders into the three‑comma club. Estimates place Luana’s personal stake at roughly 12 percent of Kalshi, valuing her net worth at about 1.3 billion dollars—wealth tied directly to equity she helped create rather than inheritance.

Kalshi itself is a big part of why her ascent matters.

Founded in 2019, the New York–based company runs a federally regulated prediction‑market exchange where users trade yes‑or‑no contracts on real‑world events, from inflation reports to elections and sports outcomes.

As of late 2025, the platform has reached around 50 billion dollars in annualized trading volume, a thousand‑fold jump from roughly 300 million the year before, according to figures cited in TechCrunch and other financial press. That hyper‑growth convinced investors that event contracts are more than a niche curiosity, and it is this conviction—expressed in billions of dollars of new capital—that turned Luana’s share of Kalshi into a billion‑dollar fortune almost overnight.

Her path to that point is unusually demanding even by founder standards. Luana grew up in Brazil and trained at the Bolshoi Theater School’s Brazilian campus, where reports say she spent up to 13 hours a day in class and rehearsal, competing for places in a program that accepts fewer than 3 percent of applicants. After a stint dancing professionally in Austria, she pivoted into academics, enrolling at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to study computer science and mathematics and later completing a master’s in engineering.

During summers she interned at major firms including Bridgewater Associates and Citadel, gaining a front‑row view of how global macro traders constantly bet on future events—but without a simple, regulated way for ordinary people to do the same.

That realization shaped Kalshi’s founding thesis and ultimately her billionaire status. Together with co‑founder Tarek Mansour, whom she met at MIT, Luana spent years persuading lawyers and U.S. regulators that a fully legal event‑trading exchange could exist under commodities law. Reports say more than 60 law firms turned them down before one agreed to help, and the company then spent roughly three years in licensing discussions with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission before gaining approval. The payoff is visible in 2025’s numbers: an 11‑billion‑dollar valuation, a 1‑billion‑dollar fresh capital injection, and a founder’s stake that makes Luana Lopes Lara not just a compelling story but a data point in how fast wealth can now be created at the intersection of finance, regulation, and software.

Business

Harvard Grads Jobless? How AI & Ghost Jobs Broke Hiring

America’s job market is facing an unprecedented crisis—and nowhere is this more painfully obvious than at Harvard, the world’s gold standard for elite education. A stunning 25% of Harvard’s MBA class of 2025 remains unemployed months after graduation, the highest rate recorded in university history. The Ivy League dream has become a harsh wakeup call, and it’s sending shockwaves across the professional landscape.

Jobless at the Top: Why Graduates Can’t Find Work

For decades, a Harvard diploma was considered a golden ticket. Now, graduates send out hundreds of résumés, often from their parents’ homes, only to get ghosted or auto-rejected by machines. Only 30% of all 2025 graduates nationally have found full-time work in their field, and nearly half feel unprepared for the workforce. “Go to college, get a good job“—that promise is slipping away, even for the smartest and most driven.

Tech’s Iron Grip: ATS and AI Gatekeepers

Applicant tracking systems (ATS) and AI algorithms have become ruthless gatekeepers. If a résumé doesn’t perfectly match the keywords or formatting demanded by the bots, it never reaches human eyes. The age of human connection is gone—now, you’re just a data point to be sorted and discarded.

AI screening has gone beyond basic qualifications. New tools “read” for inferred personality and tone, rejecting candidates for reasons they never see. Worse, up to half of online job listings may be fake—created simply to collect résumés, pad company metrics, or fulfill compliance without ever intending to fill the role.

The Experience Trap: Entry-Level Jobs Require Years

It’s not just Harvard grads who are hurting. Entry-level roles demand years of experience, unpaid internships, and portfolios that resemble a seasoned professional, not a fresh graduate. A bachelor’s degree, once the key to entry, is now just the price of admission. Overqualified candidates compete for underpaid jobs, often just to survive.

One Harvard MBA described applying to 1,000 jobs with no results. Companies, inundated by applications, are now so selective that only those who precisely “game the system” have a shot. This has fundamentally flipped the hiring pyramid: enormous demand for experience, shrinking chances for new entrants, and a brutal gauntlet for anyone not perfectly groomed by internships and coaching.

Burnout Before Day One

The cost is more than financial—mental health and optimism are collapsing among the newest generation of workers. Many come out of elite programs and immediately end up in jobs that don’t require degrees, or take positions far below their qualifications just to pay the bills. There’s a sense of burnout before careers even begin, trapping talent in a cycle of exhaustion, frustration, and disillusionment.

Cultural Collapse: From Relationships to Algorithms

What’s really broken? The culture of hiring itself. Companies have traded trust, mentorship, and relationships for metrics, optimizations, and cost-cutting. Managers no longer hire on potential—they rely on machines, rankings, and personality tests that filter out individuality and reward those who play the algorithmic game best.

AI has automated the very entry-level work that used to build careers—research, drafting, and analysis—and erased the first rung of the professional ladder for thousands of new graduates. The result is a workforce filled with people who know how to pass tests, not necessarily solve problems or drive innovation.

The Ghost Job Phenomenon

Up to half of all listings for entry-level jobs may be “ghost jobs”—positions posted online for optics, compliance, or future needs, but never intended for real hiring. This means millions of job seekers spend hours on applications destined for digital purgatory, further fueling exhaustion and cynicism.

Not Lazy—Just Locked Out

Despite the headlines, the new class of unemployed graduates is not lazy or entitled—they are overqualified, underleveraged, and battered by a broken process. Harvard’s brand means less to AI and ATS systems than the right keyword or résumé format. Human judgment has been sidelined; individuality is filtered out.

What’s Next? Back to Human Connection

Unless companies rediscover the value of human potential, mentorship, and relationships, the job search will remain a brutal numbers game—one that even the “best and brightest” struggle to win. The current system doesn’t just hurt workers—it holds companies back from hiring bold, creative talent who don’t fit perfect digital boxes.

Key Facts:

- 25% of Harvard MBAs unemployed, highest on record

- Only 30% of 2025 grads nationwide have jobs in their field

- Nearly half of grads feel unprepared for real work

- Up to 50% of entry-level listings are “ghost jobs”

- AI and ATS have replaced human judgment at most companies

If you’ve felt this struggle—or see it happening around you—share your story in the comments. And make sure to subscribe for more deep dives on the reality of today’s economy and job market.

This is not just a Harvard problem. It’s a sign that America’s job engine is running on empty, and it’s time to reboot—before another generation is locked out.

Film Industry2 weeks ago

Film Industry2 weeks agoTurning One Short Film into 12 Months of Content

Film Industry3 weeks ago

Film Industry3 weeks ago10 Ways Filmmakers Are Building Careers Without Waiting for Distributors

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week agoWhat the Epstein Files Actually Say About Jay-Z

Film Industry1 week ago

Film Industry1 week agoAI Didn’t Steal Your Job. It Revealed Who Actually Does the Work.

Film Industry2 weeks ago

Film Industry2 weeks agoHow to Write a Logline That Makes Programmers Hit Play

News1 week ago

News1 week agoCatherine O’Hara: The Comedy Genius Who Taught Us That Character Is Everything

Entertainment5 days ago

Entertainment5 days agoYou wanted to make movies, not decode Epstein. Too late.

Entertainment1 day ago

Entertainment1 day agoWhat Epstein’s Guest Lists Mean for Working Filmmakers: Who Do You Stand Next To?