Business

$1 trillion in unpaid corporate taxes sparks UN tussle on November 1, 2023 at 10:00 am Business News | The Hill

The IRS is cracking down on domestic tax evasion by going after wealthy individuals and complex private partnerships, but some of the biggest tax evaders — U.S. multinational corporations — are still exploiting legal gray areas to stash money overseas and keep it out of the government’s reach.

Fed up with a stalled international effort at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to rein in the use of tax havens and put a global corporate minimum tax into force, African countries at the United Nations are now leading a charge for greater transparency and fairness in international tax.

$1 trillion a year lost to tax havens

In 2022, profits stowed in tax havens by giant companies totaled $1 trillion, amounting to about 35 percent of foreign profits, according to the EU Tax Observatory’s 2024 global tax evasion report, published this week.

“Foreign profits are the profits made by multinational companies outside of their headquarter country – they include, for instance, the profits booked by Apple outside of the United States, by BMW outside of Germany, and by Toyota outside of Japan. In 2022, according to the best available estimates, profits shifted to tax havens totaled $1 trillion globally,” the report’s researchers found.

“The corporate tax revenue losses caused by this shifting are significant, the equivalent of nearly 10 percent of corporate tax revenues collected globally,” they noted.

The findings back up a 2021 study by the U.K.-based International Centre for Tax and Development (ICTD) that found multinationals moved about $1 trillion to tax havens in 2016.

U.S. companies do more of this profit shifting compared to their international peers, both groups of researchers found, with about half of all U.S. foreign profits being slid into tax havens, as opposed to 30 percent for non-U.S. multinationals.

“[Multinational corporations] headquartered in the United States and Bermuda are the most aggressive at shifting profits towards tax havens, while [those] headquartered in India, China, Mexico and South Africa the least,” ICTD researchers found, calling out the Cayman Islands, Luxembourg, Bermuda, Hong Kong and the Netherlands as among “the most important tax havens.”

New push to track down tax dodges

Earlier this month, Nigeria filed a draft resolution at the General Assembly on behalf of the U.N.’s group of African states to set up an intergovernmental committee on global tax rules that could effectively supplant the rich countries in the OECD as the global coordinating tax authority.

The resolution stresses “the need for all countries to work together to eliminate tax evasion, tax base erosion and profit shifting, and to ensure that all taxpayers, including multinational companies, pay taxes to the governments of countries where economic activity occurs and value is created.”

Experts say the resolution could go to a vote in mid-November, building on the momentum of a similar resolution that passed by surprise consensus in the General Assembly at the end of last year.

That resolution resulted in a report from the secretary-general that recommended that the U.N. offered the most “viable path” for actually getting a global tax agreement signed, sealed and delivered.

“Enhancing the UN role in tax-norm shaping and rule setting, fully taking into account existing multilateral and international arrangements, appears the most viable path for making international tax cooperation fully inclusive and more effective,” the report found.

The EU bemoaned the U.N. push in September, warning of a duplication of efforts and wasted time.

“It could imply reopening negotiations, potentially on issues for which promising outcomes already exist,” the European Council said. “This would be time consuming for all jurisdictions.”

Pillar One sputters in Luxembourg

Moving money around to skimp on taxes takes a significant bite out of the domestic governmental revenues of countries where multinationals operate but pay minimal tax.

That is why experts say it’s no surprise that less well-off countries should be pushing for an alternative to the OECD’s hollowed out framework, known as Pillar One.

“Pillar One, which was supposed to deal with profit shifting, has now become very, very narrow, only addressing a small part of the profits of less than 100 multinationals. Everything else is left on the old rules, which we know don’t work,” Alex Cobham, economist and chief executive of the Tax Justice Network, an international tax advocacy organization, told The Hill.

“The instruments the OECD has put forward can’t come into effect unless the United States ratifies it, and we know that the United States doesn’t have political agreement to be able to ratify,” he said. “Pillar One is pretty much dead in the water.”

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said during a meeting of finance ministers in Luxembourg last week that the process of agreeing on Pillar One could drag on into next year.

“Much of the treaty has been agreed to. … There are some matters that are important to the United States and other countries that remain unresolved,” she told reporters, as reported by Politico.

The matters “need to be resolved before the treaty can be signed, so these processes will take into next year,” she said.

No market for ‘intangibles’

The entities actually doing the work of shifting profits internationally include the “big four” accounting firms, which are statistically correlated with the use of tax havens, according to research carried out in part by Cobham.

He and his fellow researchers found a “strong correlation and causal link between the size of an [multinational enterprise’s] tax haven network and their use of the Big 4,” comprising KPMG; Deloitte; Ernst and Young; and Price Waterhouse Coopers.

The growth rate of tax haven subsidiaries is 2.9 percent higher for multinationals that employ one of the big four to file accounts compared to those firms that do not, they found.

KPMG declined to comment on the findings. Ernst and Young, Price Waterhouse Coopers and Deloitte did not respond to request for comment for this story.

The current techniques of international tax avoidance really exploded in the early 1990s, Cobham said, when the big accounting firms started playing with transactions among company subsidiaries, which happen entirely inside a given legal structure and are not subject to market forces such as price discovery.

These techniques got more advanced when applied to “intangible assets,” such as brands and intellectual property, the true value of which is known only to its owner.

“They discovered intangibles. It’s very difficult for anybody to put a price on the Google brand being sold by Alphabet to a Google subsidiary. There is no open market for this. The transaction only happens within the multinational,” he said.

The United States Mission to the United Nations, the Nigerian Mission, and the White House declined to comment.

Business, Energy & Environment, International, News, Technology, african union, corporations, international tax, Nigeria, OECD, pillar one, tax evasion, United Nations, United Nations General Assembly The IRS is cracking down on domestic tax evasion by going after wealthy individuals and complex private partnerships, but some of the biggest tax evaders — U.S. multinational corporations — are still exploiting legal gray areas to stash money overseas and keep it out of the government’s reach. Fed up with a stalled international effort…

Business

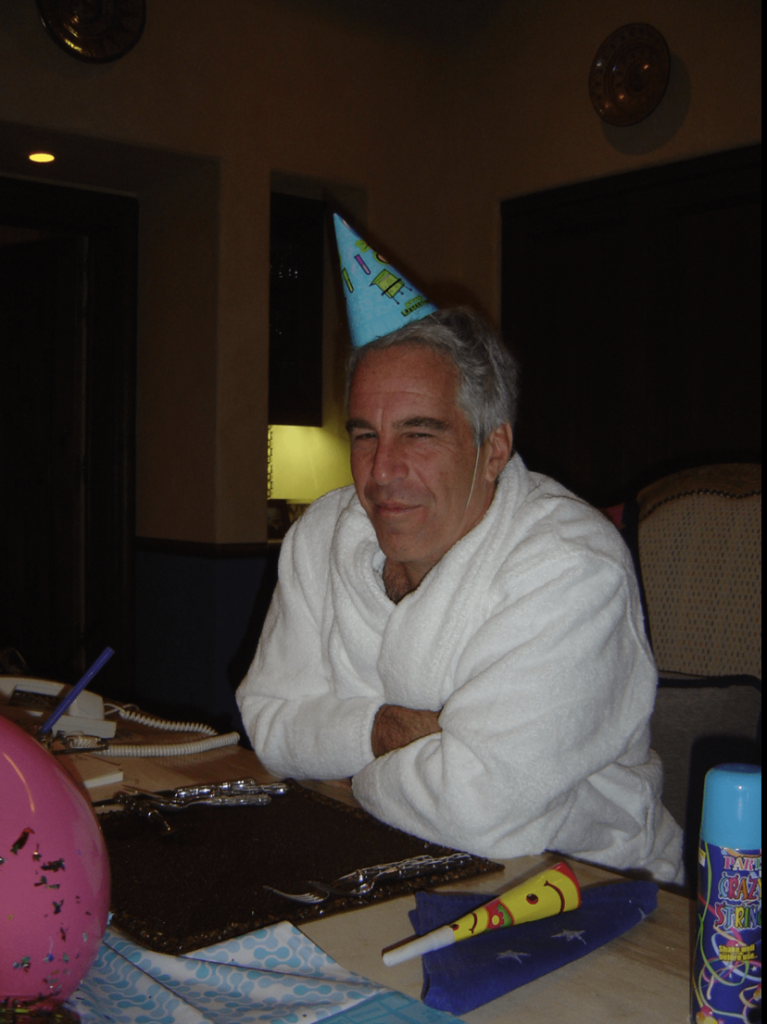

How Epstein’s Cash Shaped Artists, Agencies, and Algorithms

Jeffrey Epstein’s money did more than buy private jets and legal leverage. It flowed into the same ecosystem that decides which artists get pushed to the front, which research gets labeled “cutting edge,” and which stories about race and power are treated as respectable debate instead of hate speech. That doesn’t mean he sat in a control room programming playlists. It means his worldview seeped into institutions that already shape what we hear, see, and believe.

The Gatekeepers and Their Stains

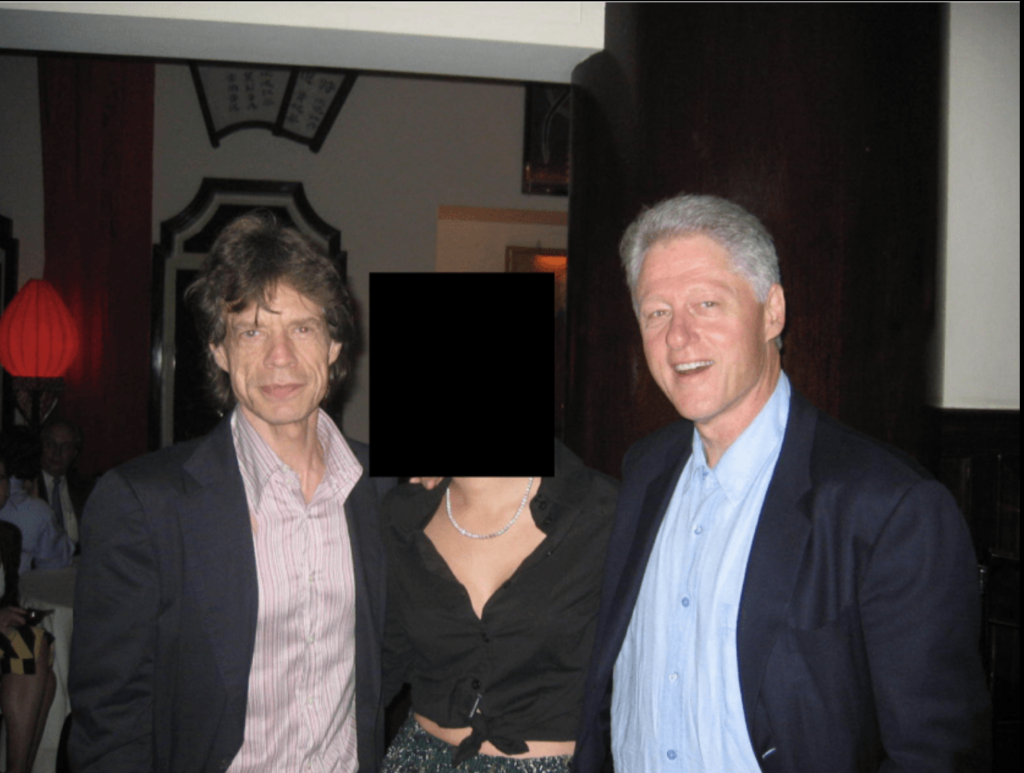

The fallout around Casey Wasserman is a vivid example of how this works. Wasserman built a powerhouse talent and marketing agency that controls a major slice of sports, entertainment, and the global touring business. When the Epstein files revealed friendly, flirtatious exchanges between Wasserman and Ghislaine Maxwell, and documented his ties to Epstein’s circle, artists and staff began to question whose money and relationships were quietly underwriting their careers.

That doesn’t prove Epstein “created” any particular star. But it shows that a man deeply entangled with Epstein was sitting at a choke point: deciding which artists get representation, which tours get resources, which festivals and campaigns happen. In an industry built on access and favor, proximity to someone like Epstein is not just gossip; it signals which values are tolerated at the top.

When a gatekeeper with that history sits between artists and the public, “the industry” stops being an abstract machine and starts looking like a web of human choices — choices that, for years, were made in rooms where Epstein’s name wasn’t considered a disqualifier.

Funding Brains, Not Just Brands

Epstein’s interest in culture didn’t end with celebrity selfies. He was obsessed with the science of brains, intelligence, and behavior — and that’s where his money begins to overlap with how audiences are modeled and, eventually, how algorithms are trained.

He cultivated relationships with scientists at elite universities and funded research into genomics, cognition, and brain development. In one high‑profile case, a UCLA professor specializing in music and the brain corresponded with Epstein for years and accepted funding for an institute focused on how music affects neural circuits. On its face, that looks like straightforward philanthropy. Put it next to his email trail and a different pattern appears.

Epstein’s correspondence shows him pushing eugenics and “race science” again and again — arguing that genetic differences explain test score gaps between Black and white people, promoting the idea of editing human beings under the euphemism of “genetic altruism,” and surrounding himself with thinkers who entertained those frames. One researcher in his orbit described Black children as biologically better suited to running and hunting than to abstract thinking.

So you have a financier who is:

- Funding brain and behavior research.

- Deeply invested in ranking human groups by intelligence.

- Embedded in networks that shape both scientific agendas and cultural production.

None of that proves a specific piece of music research turned into a specific Spotify recommendation. But it does show how his ideology was given time, money, and legitimacy in the very spaces that define what counts as serious knowledge about human minds.

How Ideas Leak Into Algorithms

There is another layer that is easier to see: what enters the knowledge base that machines learn from.

Fringe researchers recently misused a large U.S. study of children’s genetics and brain development to publish papers claiming racial hierarchies in IQ and tying Black people’s economic outcomes to supposed genetic deficits. Those papers then showed up as sources in answers from large AI systems when users asked about race and intelligence. Even after mainstream scientists criticized the work, it had already entered both the academic record and the training data of systems that help generate and rank content.

Epstein did not write those specific papers, but he funded the kind of people and projects that keep race‑IQ discourse alive inside elite spaces. Once that thinking is in the mix, recommendation engines and search systems don’t have to be explicitly racist to reproduce it. They simply mirror what’s in their training data and what has been treated as “serious” research.

Zoomed out, the pipeline looks less like a neat conspiracy and more like an ecosystem:

- Wealthy men fund “edgy” work on genes, brains, and behavior.

- Some of that work revives old racist ideas with new data and jargon.

- Those studies get scraped, indexed, and sometimes amplified by AI systems.

- The same platforms host and boost music, video, and news — making decisions shaped by engagement patterns built on biased narratives.

The algorithm deciding what you see next is standing downstream from all of this.

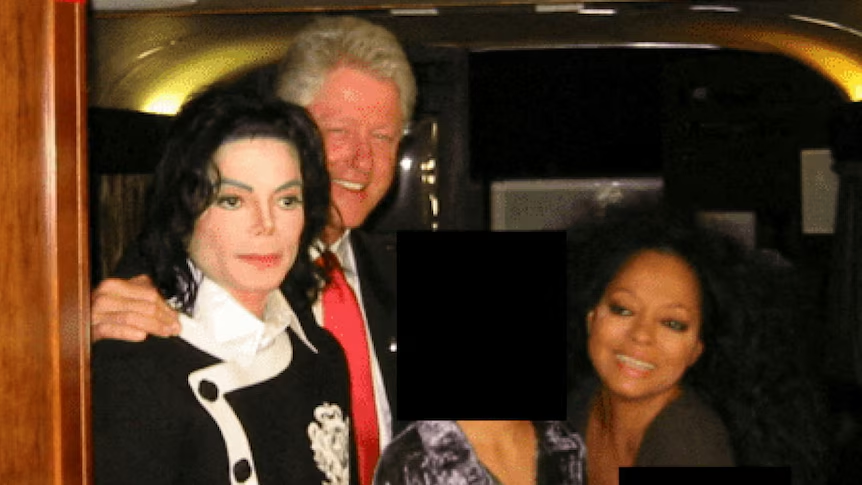

The Celebrity as Smoke Screen

Epstein’s contact lists are full of directors, actors, musicians, authors, and public intellectuals. Many now insist they had no idea what he was doing. Some probably didn’t; others clearly chose not to ask. From Epstein’s perspective, the value of those relationships is obvious.

Being seen in orbit around beloved artists and cultural figures created a reputational firewall. If the public repeatedly saw him photographed with geniuses, Oscar winners, and hit‑makers, their brains filed him under “eccentric patron” rather than “dangerous predator.”

That softens the landing for his ideas, too. Race science sounds less toxic when it’s discussed over dinner at a university‑backed salon or exchanged in emails with a famous thinker.

The more oxygen is spent on the celebrity angle — who flew on which plane, who sat at which dinner — the less attention is left for what may matter more in the long run: the way his money and ideology were welcomed by institutions that shape culture and knowledge.

What to Love, Who to Fear

The point is not to claim that Jeffrey Epstein was secretly programming your TikTok feed or hand‑picking your favorite rapper. The deeper question is what happens when a man with his worldview is allowed to invest in the people and institutions that decide:

- Which artists are “marketable.”

- Which scientific questions are “important.”

- Which studies are “serious” enough to train our machines on.

- Which faces and stories are framed as aspirational — and which as dangerous.

If your media diet feels saturated with certain kinds of Black representation — hyper‑visible in music and sports, under‑represented in positions of uncontested authority — while “objective” science quietly debates Black intelligence, that’s not random drift. It’s the outcome of centuries of narrative work that men like Epstein bought into and helped sustain.

No one can draw a straight, provable line from his bank account to a specific song or recommendation. But the lines he did draw — to elite agencies, to brain and music research, to race‑obsessed science networks — are enough to show this: his money was not only paying for crimes in private. It was also buying him a seat at the tables where culture and knowledge are made, where the stories about who to love and who to fear get quietly agreed upon.

A Challenge to Filmmakers and Creatives

For anyone making culture inside this system, that’s the uncomfortable part: this isn’t just a story about “them.” It’s also a story about you.

Filmmakers, showrunners, musicians, actors, and writers all sit at points where money, narrative, and visibility intersect. You rarely control where the capital ultimately comes from, but you do control what you validate, what you reproduce, and what you challenge.

Questions worth carrying into every room:

- Whose gaze are you serving when you pitch, cast, and cut?

- Which Black characters are being centered — and are they full humans or familiar stereotypes made safe for gatekeepers?

- When someone says a project is “too political,” “too niche,” or “bad for the algorithm,” whose comfort is really being protected?

- Are you treating “the industry” as a neutral force, or as a set of human choices you can push against?

If wealth like Epstein’s can quietly seep into agencies, labs, and institutions that decide what gets made and amplified, then the stories you choose to tell — and refuse to tell — become one of the few levers of resistance inside that machine. You may not control every funding source, but you can decide whether your work reinforces a world where Black people are data points and aesthetics, or one where they are subjects, authors, and owners.

The industry will always have its “gatekeepers.” The open question is whether creatives accept that role as fixed, or start behaving like counter‑programmers: naming the patterns, refusing easy archetypes, and building alternative pathways, platforms, and partnerships wherever possible. In a landscape where money has long been used to decide what to love and who to fear, your choices about whose stories get light are not just artistic decisions. They are acts of power.

Business

New DOJ Files Reveal Naomi Campbell’s Deep Ties to Jeffrey Epstein

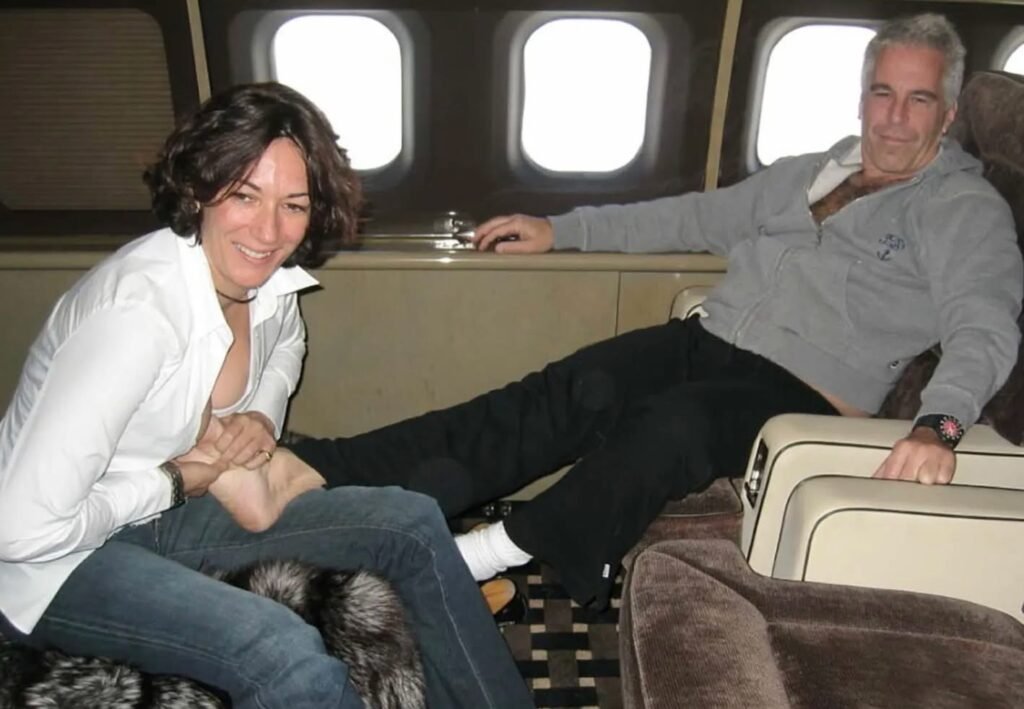

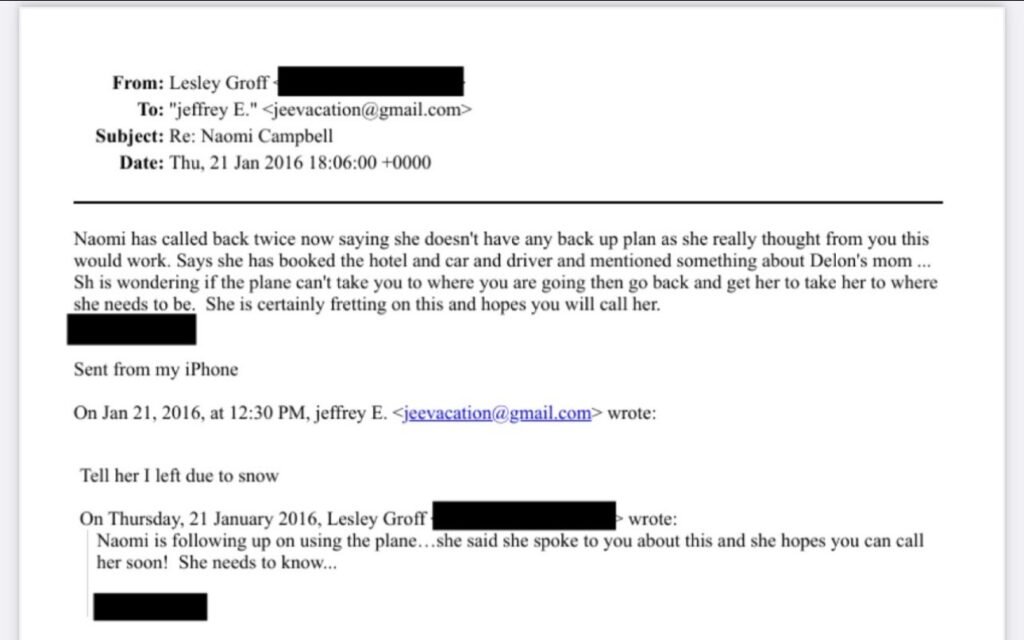

In early 2026, the global conversation surrounding the “Epstein files” has reached a fever pitch as the Department of Justice continues to un-redact millions of pages of internal records. Among the most explosive revelations are detailed email exchanges between Ghislaine Maxwell and Jeffrey Epstein that directly name supermodel Naomi Campbell. While Campbell has long maintained she was a peripheral figure in Epstein’s world, the latest documents—including an explicit message where Maxwell allegedly offered “two playmates” for the model—have forced a national re-evaluation of her proximity to the criminal enterprise.

The Logistics of a High-Fashion Connection

The declassified files provide a rare look into the operational relationship between the supermodel and the financier. Flight logs and internal staff emails from as late as 2016 show that Campbell’s travel was frequently subsidized by Epstein’s private fleet. In one exchange, Epstein’s assistants discussed the urgency of her travel requests, noting she had “no backup plan” and was reliant on his jet to reach international events.

This level of logistical coordination suggests a relationship built on significant mutual favors, contrasting with Campbell’s previous descriptions of him as just another face in the crowd.

In Her Own Words: The “Sickened” Response

Campbell has not remained silent as these files have surfaced, though her defense has been consistent for years. In a widely cited 2019 video response that has been recirculated amid the 2026 leaks, she stated, “What he’s done is indefensible. I’m as sickened as everyone else is by it.” When confronted with photos of herself at parties alongside Epstein and Maxwell, she has argued against the concept of “guilt by association,” telling the press:

She has further emphasized her stance by aligning herself with those Epstein harmed, stating,

“I stand with the victims. I’m not a person who wants to see anyone abused, and I never have been.””

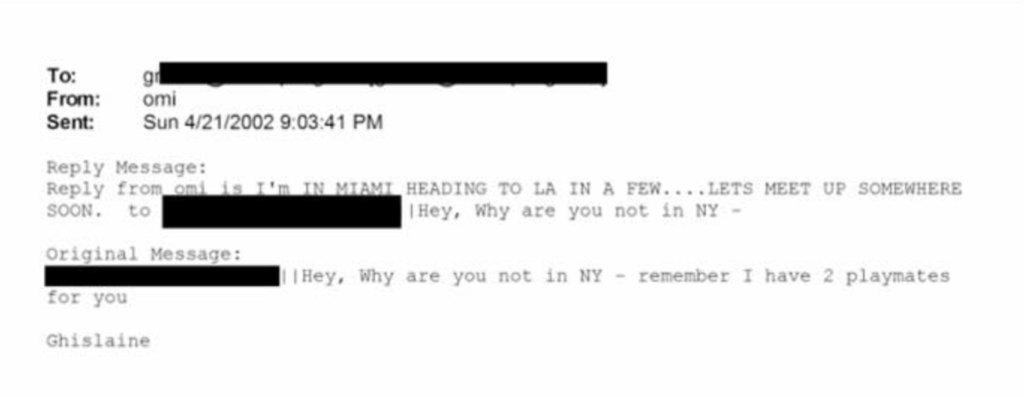

The Mystery of the “Two Playmates”

The most damaging piece of evidence in the recent 2026 release is an email where Maxwell reportedly tells Epstein she has “two playmates” ready for Campbell.

While the context of this “offer” remains a subject of intense debate—with some investigators suggesting it refers to the procurement of young women for social or sexual purposes—Campbell’s legal team has historically dismissed such claims as speculative. However, for a public already wary of elite power brokers, the specific wording used in these private DOJ records has created a “stop-the-scroll” moment that is proving difficult for the fashion icon to move past.

A Reputation at a Crossroads

As a trailblazer in the fashion industry, Campbell is now navigating a period where her professional achievements are being weighed against her presence in some of history’s most notorious social circles. The 2026 files don’t just name her; they place her within a broader system where modeling agents and scouts allegedly groomed young women under the guise of high-fashion opportunities. Whether these records prove a deeper complicity or simply illustrate the unavoidable overlap of the 1% remains the central question of the ongoing DOJ investigation.

Business

Google Accused Of Favoring White, Asian Staff As It Reaches $28 Million Deal That Excludes Black Workers

Google has tentatively agreed to a $28 million settlement in a California class‑action lawsuit alleging that white and Asian employees were routinely paid more and placed on faster career tracks than colleagues from other racial and ethnic backgrounds.

- A Santa Clara County Superior Court judge has granted preliminary approval, calling the deal “fair” and noting that it could cover more than 6,600 current and former Google workers employed in the state between 2018 and 2024.

How The Discrimination Claims Emerged

The lawsuit was brought by former Google employee Ana Cantu, who identifies as Mexican and racially Indigenous and worked in people operations and cloud departments for about seven years. Cantu alleges that despite strong performance, she remained stuck at the same level while white and Asian colleagues doing similar work received higher pay, higher “levels,” and more frequent promotions.

Cantu’s complaint claims that Latino, Indigenous, Native American, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and Alaska Native employees were systematically underpaid compared with white and Asian coworkers performing substantially similar roles. The suit also says employees who raised concerns about pay and leveling saw raises and promotions withheld, reinforcing what plaintiffs describe as a two‑tiered system inside the company.

Why Black Employees Were Left Out

Cantu’s legal team ultimately agreed to narrow the class to employees whose race and ethnicity were “most closely aligned” with hers, a condition that cleared the path to the current settlement.

The judge noted that Black employees were explicitly excluded from the settlement class after negotiations, meaning they will not share in the $28 million payout even though they were named in earlier versions of the case. Separate litigation on behalf of Black Google employees alleging racial bias in pay and promotions remains pending, leaving their claims to be resolved in a different forum.

What The Settlement Provides

Of the $28 million total, about $20.4 million is expected to be distributed to eligible class members after legal fees and penalties are deducted. Eligible workers include those in California who self‑identified as Hispanic, Latinx, Indigenous, Native American, American Indian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and/or Alaska Native during the covered period.

Beyond cash payments, Google has also agreed to take steps aimed at addressing the alleged disparities, including reviewing pay and leveling practices for racial and ethnic gaps. The settlement still needs final court approval at a hearing scheduled for later this year, and affected employees will have a chance to opt out or object before any money is distributed.

H2: Google’s Response And The Broader Stakes

A Google spokesperson has said the company disputes the allegations but chose to settle in order to move forward, while reiterating its public commitment to fair pay, hiring, and advancement for all employees. The company has emphasized ongoing internal audits and equity initiatives, though plaintiffs argue those efforts did not prevent or correct the disparities outlined in the lawsuit.

For many observers, the exclusion of Black workers from the settlement highlights the legal and strategic complexities of class‑action discrimination cases, especially in large, diverse workplaces. The outcome of the remaining lawsuit brought on behalf of Black employees, alongside this $28 million deal, will help define how one of the world’s most powerful tech companies is held accountable for alleged racial inequities in pay and promotion.

Entertainment2 weeks ago

Entertainment2 weeks agoWhat the Epstein Files Actually Say About Jay-Z

Film Industry4 weeks ago

Film Industry4 weeks agoTurning One Short Film into 12 Months of Content

Film Industry4 weeks ago

Film Industry4 weeks ago10 Ways Filmmakers Are Building Careers Without Waiting for Distributors

Film Industry3 weeks ago

Film Industry3 weeks agoAI Didn’t Steal Your Job. It Revealed Who Actually Does the Work.

Entertainment2 weeks ago

Entertainment2 weeks agoWhat Epstein’s Guest Lists Mean for Working Filmmakers: Who Do You Stand Next To?

Film Industry3 weeks ago

Film Industry3 weeks agoHow to Write a Logline That Makes Programmers Hit Play

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoCatherine O’Hara: The Comedy Genius Who Taught Us That Character Is Everything

Entertainment3 days ago

Entertainment3 days agoYou wanted to make movies, not decode Epstein. Too late.